권호기사보기

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 대표형(전거형, Authority) | 생물정보 | 이형(異形, Variant) | 소속 | 직위 | 직업 | 활동분야 | 주기 | 서지 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 연구/단체명을 입력해주세요. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

* 주제를 선택하시면 검색 상세로 이동합니다.

Title Page

Contents

Abstract of the Dissertation 5

PART 1-1. Analysis of Tan Dun's "Concerto for String Orchestra and Pipa" 8

Introduction 8

Pentatonic Melodies 11

Sliding Notes 15

Percussion Imitation 18

Corporeal Exercises 22

Musical Quotations from Two Different Cultures 26

Sounds of Tuning 28

Conclusion 30

PART 1-2. Analysis of Unsuk Chin's "Šu" for Sheng and Orchestra 32

Introduction 32

Structure in Arch Form 33

Section 1 34

Section 2 40

Section 3 44

Section 4 46

Conclusion 47

Summary and Conclusion 49

Appendix: Tempos of "Šu" for Sheng and Orchestra 52

Bibliography 56

Breakthrough! Concerto for Ajaeng and Orchestra 58

Figure 1. Melody 1 at mm.41-43, first movement, on pipa 12

Figure 2. Two pentatonic scales in Melody 1 12

Figure 3. Melody 2 at mm.19-30, first movement, on viola 13

Figure 4. The pentatonic scale of Melody 2 13

Figure 5. Melody 3 at mm.35-60, second movement, on violin 1 13

Figure 6. Two pentatonic scales of Melody 3 14

Figure 7. Melody 4, "Little Cabbage" at mm.1-7, third movement, on violin 14

Figure 8. The pentatonic scale of Melody 4 "Little Cabbage" 15

Figure 9. The transcript of the recording of "Little Cabbage" in 5/4 meter 15

Figure 10. Sliding motive 1 at mm. 1-2, first movement, on cello 16

Figure 11. Sliding motive 1 at mm. 5, first movement 16

Figure 12. Sliding notes at mm. 7-10, second movement 17

Figure 13. Sliding motive 2 at mm. 47-53, second movement, on second violin 17

Figure 14. Sliding motive 2 at mm. 60-67, fourth movement 18

Figure 15. mm. 19-26, first movement 20

Figure 16. mm. 15-26, second movement 21

Figure 17. Foot stomping at the beginning of the first movement. X notes indicate... 23

Figure 18. Shouting "yao" at mm.143-149, second movement 25

Figure 19. Shouting "yao" at mm.98, fourth movement 25

Figure 20. Breathing out at mm. 190, second movement 26

Figure 21. Bach Prelude c-sharp minor from Book I of The Well Tempered Clavier, mm.1-11 27

Figure 22. Notated tuning practice in the last measure of the second movement 29

Figure 23. Meter change pattern in Section 1 39

Figure 24. Tempo changes in Section 2 at the rate of the sixteenth note 41

Figure 25. Tempo changes in Section 3 and 4 at the rate of the sixteenth note 45

Figure 26. Harp passage at mm. 318-319 45

My dissertation consists of two parts: a music composition, a Concerto for So-Ajaeng and Orchestra entitled "Breakthrough," and an essay presenting analysis of two concertos - Tan Dun's "Concerto for String Orchestra and Pipa" (1999) and Unsuk Chin's "Šu for Sheng and Orchestra" (2009). For a long time I have worked to make connections between traditional Korean and Western classical influences in my music. My dissertation piece continues this effort. A concerto for a Korean instrument solo with Western orchestra seemed an ideal genre in which to move forward in this direction. Korean So-Ajaeng is chosen for solo instrument because of its penetrating and strong sounds that can compete with full orchestra.

Both Tan Dun and Unsuk Chin composed for a Chinese solo instrument with Western orchestra, but the composers' musical and philosophical approaches to Asian traditions in their pieces are quite different. On the one hand, Tan Dun quotes from both Western and Chinese traditions strongly and directly. Melodies and styles from both traditions freely cross over the cultural borders and are often overlaid. On the other hand, Unsuk Chin resists any explicit reference to either Asian or Western tradition. Rather, she focuses on the technical characteristics of the sheng - particularly its ability to build and sustain multi-voice chords almost indefinitely. She takes this technical capability as a model for her writing for the orchestra. Tan Dun's embrace of cultural references and Unsuk Chin's avoidance of them could be said to represent extremes of a continuum of composers' approaches and philosophies toward multicultural composition.

내 논문은 1) 음악 작곡, 소아쟁과 오케스트라를 위한 협주곡 'Breakthrough'와 2) 탄둔의 "Concerto for String Orchestra and Pipa" (1999)와 진은숙의 "Šu for Sheng and Orchestra" (2009) 두 협주곡에 대한 분석을 발표하는 에세이로 구성되어 있다. 오랫동안 나는 내 음악에서 한국 전통과 서양 고전음악 영향을 연결시키기 위해 노력해왔다. 나의 논문은 이러한 노력의 연장선이다. 서양 오케스트라의 반주에 한국 악기를 독주로 하는 협주곡은 이런 방향으로 나아가는 이상적인 장르로 보였다. 오케스트라에 대항할 만큼 관통적이고 강한 음색을 가진 소아쟁을 독주 악기로 선택했다.

탄둔과 진은숙은 모두 서양 관현악단과 함께 중국 독주 악기를 위해 작곡했지만, 작곡가의 아시아 전통에 대한 음악적, 철학적인 접근은 전혀 다르다. 탄둔은 서양과 중국 전통 어법을 강하고 직접적으로 인용한다. 두 전통의 멜로디와 스타일이 자유롭게 문화적 경계를 넘나들며 겹치는 경우가 많다. 반면에 진은숙은 아시아 전통이나 서양 전통에 대한 어떠한 명시적인 언급을 거부한다. 대신에 그녀는 중국 sheng의 기술적 특징, 특히 다중 음성 화음을 거의 무한정 구축하고 유지하는 능력에 초점을 맞춘다. 그녀는 이 특징을 오케스트라 작곡의 모델로 삼는다. 탄둔의 문화적 참조에 대한 포용과 진은숙의 회피는 다문화 작곡에 대한 작곡가들의 접근법과 철학의 연속적인 극단을 보여준다고 할 수 있다.*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

| *전화번호 | ※ '-' 없이 휴대폰번호를 입력하세요 |

|---|

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 번호 | 발행일자 | 권호명 | 제본정보 | 자료실 | 원문 | 신청 페이지 |

|---|

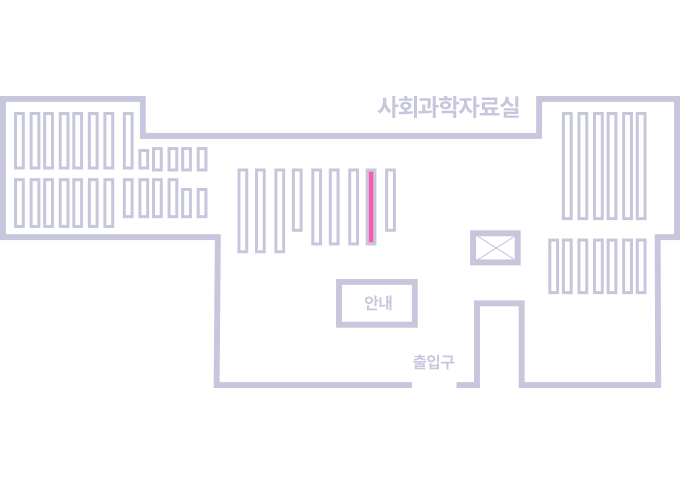

도서위치안내: / 서가번호:

우편복사 목록담기를 완료하였습니다.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

저장 되었습니다.