권호기사보기

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 대표형(전거형, Authority) | 생물정보 | 이형(異形, Variant) | 소속 | 직위 | 직업 | 활동분야 | 주기 | 서지 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 연구/단체명을 입력해주세요. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

* 주제를 선택하시면 검색 상세로 이동합니다.

목차

르네상스와 우리 인문학 / 박상익 1

번역으로 꽃핀 이슬람 문명 1

번역으로 근대를 연 일본과 빈약한 한글 콘텐츠 3

우리가 르네상스를 말할 상황인가? 6

인문학·르네상스·소통 8

정체성의 발견과 새 역사의 창조 10

인용문헌 13

Abstract 14

The Saracens, with no native philosophy and science of their own, but with marvellous power of assimilating the cultures of others, quickly absorbed whatever they found in Western Asia. Arabic translations were made directly from the Greeks as well as from Syriac and Hebrew. To their Greek inheritance the Arabs added something of their own. Certain of the caliphs especially favored learning, while the universal diffusion of the Arabic language made communication easy and spread a common culture through Islam, regardless of political division.

As the Crusaders discovered, this "infidal" culture was clearly more advanced in significant respects than that of the Latin West. Little wonder that the Arabs considered the Crusaders barbarian raiders, or that Europeans looked upon the Islamic world with that peculiar combination of fear and admiration. The most important channel by which the new learning reached Western Europe ran through the Spanish peninsula. The chief center was Toledo. From Spain came the philosophy and natural science of Aristotle and his Arabic commentators in the form which was to transform European thought in the thirteenth century.

The indebtedness of the Western world to the Arabs is well illustrated in the scientific and commercial terms which its various languages have borrowed untranslated from the Arabics. Words like algebra, zero, cipher tell their own tale. Beginning in the 1150s, Latin editions of the rediscovered writings began to flood the libraries of Europe's scholars. The output of the translation centers in Spain, Provence, and Italy was enormous, numbering in the thousands of manuscript. Aristotle's recovered work was the key to further developments that would turn Europe from a remote, provincial region into the very heartland of an expansive global civilization. It is the Renaissance of the Twelfth Century, which is also known as the Medieval Renaissance. We should let this be a good lesson to ourselves.| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 목차 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 르네상스와 우리 인문학 | 박상익 | pp.1-15 |

|

보기 |

| (The)origin and attributes of typology of the medieval era | Yi-Kyun No | pp.17-28 |

|

보기 |

| 존 던의 「님의 침묵」과 한용운의 「님의 침묵」 | 이상엽 | pp.29-66 |

|

보기 |

| (A)study on the cyclic and linear patterns in Lycidas | Byung-Eun Lee | pp.67-81 |

|

보기 |

| 타락의 언술을 통해 본 이브의 청교도 이미지 :밀턴의 『실낙원』 | 양병현 | pp.83-106 |

|

보기 |

| "어느 쪽으로 달아나도 지옥, 내 자신이 지옥이니" :『실낙원』, 욕망이라는 이름의 비극 | 이정영 | pp.107-129 |

|

보기 |

| 존 밀턴의 『아레오파기티카』에 나타난 "현명한 독자"와 검열, 그리고 자유의지 | 최재헌 | pp.131-157 |

|

보기 |

| 『앤 킬리그루양을 추모하며』와 드라이든의 이상적 시인관 | 김옥수 | pp.159-173 |

|

보기 |

| 번호 | 참고문헌 | 국회도서관 소장유무 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | “저자를 만나다: 강명관 부산대교수(한문학과).” 교수신문2007년 10월 1일자. | 미소장 |

| 2 | 감염된 언어 . 서울: 개마고원, 1992. | 미소장 |

| 3 | 김수영 전집: 산문 . 서울: 민음사, 2002. | 미소장 |

| 4 | 동양학 어떻게 할 것인가 . 서울: 민음사, 1984. | 미소장 |

| 5 | 밀턴 평전: 불굴의 이상주의자 . 서울: 푸른역사, 2008. | 미소장 |

| 6 | (2006)번역은 반역인가. 서울: 푸른역사. | 미소장 |

| 7 | “만물상: 영어와 일본인” 조선일보 2008년 12월 13일자. | 미소장 |

| 8 | English As a Global Language. 1998. 유영난 역. 왜 영어가 세계어인가 . 서울: 코기토, 2002. | 미소장 |

| 9 | Il Nome Della Rosa. 1980. 이윤기 역. 장미의 이름. 서울: 열린책들, 1986. | 미소장 |

| 10 | Aristotle's Children. New York: Harcourt. 2003. | 미소장 |

| 11 | Arts of Living. 2003. 정연희 역. 인문학의 즐거움 . 서울: 휴먼앤북스, 2008. | 미소장 |

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

| *전화번호 | ※ '-' 없이 휴대폰번호를 입력하세요 |

|---|

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 번호 | 발행일자 | 권호명 | 제본정보 | 자료실 | 원문 | 신청 페이지 |

|---|

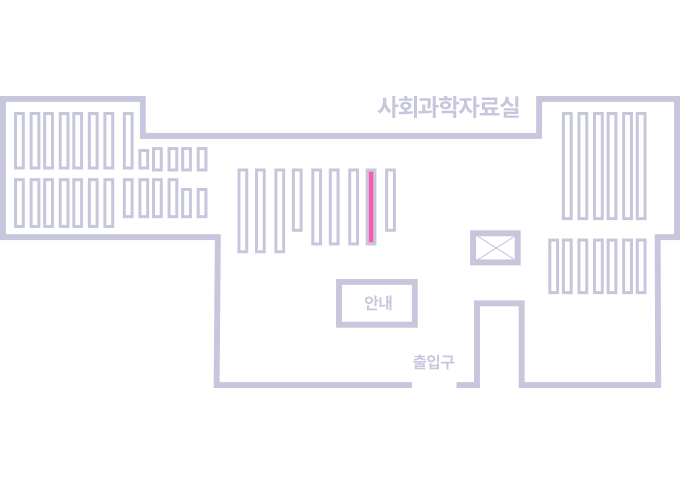

도서위치안내: 정기간행물실(524호) / 서가번호: 국내05

2021년 이전 정기간행물은 온라인 신청(원문 구축 자료는 원문 이용)

우편복사 목록담기를 완료하였습니다.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

저장 되었습니다.