권호기사보기

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 대표형(전거형, Authority) | 생물정보 | 이형(異形, Variant) | 소속 | 직위 | 직업 | 활동분야 | 주기 | 서지 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 연구/단체명을 입력해주세요. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

* 주제를 선택하시면 검색 상세로 이동합니다.

The concept of a 'National school' seems to be highly controversial. The very term 'school' is ambiguous and is used by music historians in various, to refer both to geographic centers, and to type of music as well as in terms of a national group. Usually this concept implies a distinctive style of music, within which other stylistic categories can be distinguished. Above all, however, it is associated with a cycle of pupils, trained under one master, and grouped around a prominent figure.

In the 19th-century the crystallization of a national character in art occurred in the new socio-political situation arising from the French Revolution. The victory of 'Third Estate' as the presentative of wide social strata over the cosmopolitan aristocracy contributed to a marked intensification of the feeling of national consciousness, the deciding factor in the question of whether a certain collectivity of people forms a nation.

Accepting as one of the basic features of 19th-century art the strengthening of the national element, we ought to widen the concept of 'national school' to include the music of all the countries of Europe. This does not mean that 19th-century music developed in closed national circles; it drew stronglt on the whole of European art. The demand for nationalism in art did not imply isolationism in native art. The concept of a 'national school' is a historical category typical of the music of the 19th-century. It applies not only to the manifestations of a national style, symptomatic of that century, obviously perceptible in compositions in which the composer transforms the folk music of his country, or clearly refers to his native artistic tradition.

A clearly defined 'Polish national school' stance appeared in Poland in the 19th-century is as follows;In solo and chamber instrumental music, thanks to his master of the composer's skill, Jozef Elsner, Frederic Chopin took advantage of folk creativity I an unparalleled way. In his mazurkas and polonaises he introduced the Polish national style in music. Karol Szymanowski, who was prominent in the pursuit of Chopin's idea, fully realized this.

In vocal music, the works of Stanislaw Moniuszko selected text by the composer from the works of Mickiewicz, Malczewski for his indisputable Polishness he relied not so much on musical devices the dance rhythms of folk music. The work of Oskar Kolberg not only played a fundamental role in the history of ethnography, but also had a decisive influence on the direction in which music turned in the second half of the 19th-century. Abandoning his practice of adding piano accompaniments to the folk melodies, as he had done in his first publications, Oskar Kolberg presented in authentic form over 13,000 folk songs from various regions of Poland.

In Opera, Stanislaw Moniuszko's opera, Historical opera only gained the designation national when a folk thread was introduced next to the historical thread; the more folk elements it contained, the more national it was considered to be. It is revealed above all in the introduction of Polish dances, masterfully presented in Stanislaw Moniuszko's opera, in the wider utilization of folk rhythms in vocal, and especially choral, parts, and in the modification of folk melodies. His role in Poland at that time was like Glinka in Russia and Smetana in Bohemia.

These four artistic individuals, Frederic Chopin, Stanislaw Moniuszko, Oskar Kolberg, Karol Szymanowski, form as it were the essence of the 'Polish national school; The most typical features of 19th-century Polish music culture are concentrated in their activities. Chopin created the model for approaching the wealth of folk music and raised Polish piano music to a European level; Moniuszko established the line of development for the national opera and song; 'Songs of the Polish Peasantry', collected by Kolberg, became a boundless source of artistic inspiration; Szymanowski, a father of Polish contemporary music in the beginning of 20th-century.| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 목차 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 정치이데올로기와 음악비평 : 푸치니 오페라 평가에서 드러난 이중적 잣대 분석 | 박윤경 | pp.5-26 |

|

|

| 창작 국악관현악의 총보 기보법 연구 | 양미지 | pp.27-53 |

|

|

| 스트라빈스키의 초기 음열음악 <셰익스피어에 의한 세 개의 노래>에 나타난 조직성 | 안선현 | pp.55-74 |

|

|

| 악극이 한국오페라 계에 끼친 영향 연구 | 전정임 | pp.75-98 |

|

|

| 19세기 폴란드 국민악파의 작품에 관통하는 민족적 표현양식 | 이승선 | pp.99-119 |

|

|

| 성종조 궁정 나례 중 관나(觀儺)의 현대적 재현을 위한 3D 제작과 의의 | 윤아영 | pp.121-149 |

|

|

| 음악교사효능감의 직무수행 영역 확인 및 구성요인 탐색 | 최미영 | pp.151-176 |

|

|

| '다문화 음악교육', '다인종 음악교육', '세계음악 교육'이라는 용어들 : 학술적 문헌 속의 쓰임새 비판 | 이아니스 미랄리스 [저] ; 박미경 역 | pp.177-199 |

| 번호 | 참고문헌 | 국회도서관 소장유무 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baculewski Krzysztof. 1996 Historia Myzyki Polskiej. Sutkowski ed. Warszawa, 1996. | 미소장 |

| 2 | Chechlinska Zofia, Steszewski Jan. 1986 Polish Musicological Studies vol. 2 Krakow, 1986. | 미소장 |

| 3 | Chominski Jozef. 1968 Muzyka Polska Ludowej. Warszawa. 1968. | 미소장 |

| 4 | Chominski Jozef. i Lissa Zofia. 1957 Kultura muzyczna Polski Ludowej Krakow, PWM, 1957. | 미소장 |

| 5 | Einstein Alfred. 1947 Music in the Romantic Era: A History of Musical Thought in the 19th Century .New York, 1947. | 미소장 |

| 6 | Golaszewska Maria. 1984 Estetyka i antyestetyka. Warszawa, 1984. | 미소장 |

| 7 | Helman Zofia. 1986 "Profile of the life and work of Zofia Lissa." Polsh Musicological Studies, vol. 3, Krakow, 1986. | 미소장 |

| 8 | Jarocinski Stefan. 1979 “Ideologie Romantyczne.” Krakow, PWM, 1979. | 미소장 |

| 9 | Lempicki Zygmunt. 1959 “Renesans, Oswiecenie, Romantyzm.” Warszawa, 1929. | 미소장 |

| 10 | Maleckiej Teresy. 1992 Krakowska Szkola Kompozytorska 1888-1988. Academii Muzycznej w Krakowie. 1992. | 미소장 |

| 11 | Meyer Peter. 1973 Historia sztuki europejskiej. vol. 1, 2. Warszawa, 1973. | 미소장 |

| 12 | Moniuszko Stanislaw. 1857 A few remarks on J. I. Kraszewski's Letters to the Gazeta Warszawska Ruch Muzyczny, vol. 11, Krakow, 1857 | 미소장 |

| 13 | Norman Davies. 1981 A History of Poland, Oxford, Oxford Univ. Press, 1981. | 미소장 |

| 14 | Rudzinski Witold. 1969 I cite from Stanislaw Moniuszko. Listy Zebrane Cracow, 1969 | 미소장 |

| 15 | Skrzynska Anna. 1971 “Collage w muzyce ‘Forum Musicum’ ” nr, 10. Krakow, 1971. | 미소장 |

| 16 | Sobieski Marian. 1961 Oskar Kolberg as Music Folklorist. vol. 1, Cracow-Wroclaw, 1961. | 미소장 |

| 17 | Sokolowska Jadwiga. 1971 “Spory o barok. W poszukiwaniu modelu epoki.” Warszawa, 1971. | 미소장 |

| 18 | Zielinski Andrzej. 1969 “Nation and Nationality in Polish Literature and Journalism in the Years 1815-1831.” Wroclaw, 1969 | 미소장 |

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

| *전화번호 | ※ '-' 없이 휴대폰번호를 입력하세요 |

|---|

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 번호 | 발행일자 | 권호명 | 제본정보 | 자료실 | 원문 | 신청 페이지 |

|---|

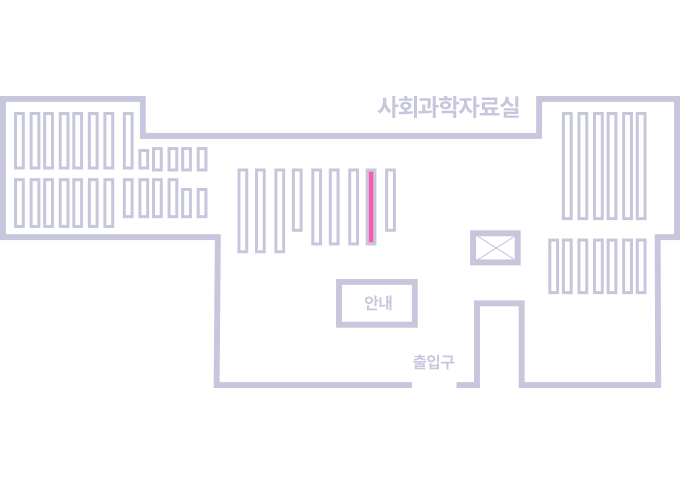

도서위치안내: 정기간행물실(524호) / 서가번호: 국내08

2021년 이전 정기간행물은 온라인 신청(원문 구축 자료는 원문 이용)

우편복사 목록담기를 완료하였습니다.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

저장 되었습니다.