권호기사보기

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 대표형(전거형, Authority) | 생물정보 | 이형(異形, Variant) | 소속 | 직위 | 직업 | 활동분야 | 주기 | 서지 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 연구/단체명을 입력해주세요. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

* 주제를 선택하시면 검색 상세로 이동합니다.

The Merchant of Venice has a contrasting structure with a number of juxtaposed and contrasting elements in it. Shakespeare leads us to see the duplicity and the dualistic viewpoint of human beings through the contrasting attitudes of a Jew and a Christian. One of the most distinguished contrasting things in the juxtaposed and contrasting elements of Venice and Belmont is the value of the visible things and the invisible things.

Venice could be considered a center of commercial trades, while Belmont as a center of romantic love. In Venice, poor Bassanio wants to go to Belmont to woo the rich heiress Portia and to do so he borrows money from his friend Antonio. Antonio doesn’t have cash to afford the needs of Bassanio so he borrows the money from the Jew, Shylock. Antonio shows extreme friendship by risking his own life, while the Jew Shylock wants to have his daughter, Jessica, back as dead with his lost bags of ducats and precious stones. In Venice, the value of visible things is focused on the job of usurer and a bond that Shylock maintains to the end against a Christian, Antonio. In Belmont, suitors come from all over the world to court Portia according to the will of her dead father. It states that who chooses the right casket can marry Portia. One of the suitors, Bassanio chooses the visibly most invaluable lead casket which holds the most valuable picture of Portia.

In Venice, Shylock is sentenced to lose all his possessions instead of succeeding in taking the vengeance he desires while in Belmont Bassanio succeeds in marrying Portia and receiving happy news of Antonio’s recovery of his wealth. In Venice the usurer Shylock could not keep his wealth or the daughter that he has tried hard to keep, while in Belmont Bassanio gets the fortune without effort or virtue. Portia is supposed to follow her father’s will but she lets Bassanio get a hint to choose the right casket by her own will. These contrasting elements deliver the message that life depends not only on one’s own will but also on Fortune.

The drama ends with the ado about rings that Bassanio and Gratiano gave to the disguised lawyer and the clerk, Portia and Nerrisa. Through this final scene we get the writer’s message that the law or the ring is the only sign of justice or love, not the substantial entity itself. Real value is invisible justice and love, not the mere sign of justice, the law and sign of love, the ring. As mentioned above, the theme ideas of The Merchant of Venice are revealed effectively through the juxtaposed and contrast elements of Venice and Belmont.*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

| *전화번호 | ※ '-' 없이 휴대폰번호를 입력하세요 |

|---|

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 번호 | 발행일자 | 권호명 | 제본정보 | 자료실 | 원문 | 신청 페이지 |

|---|

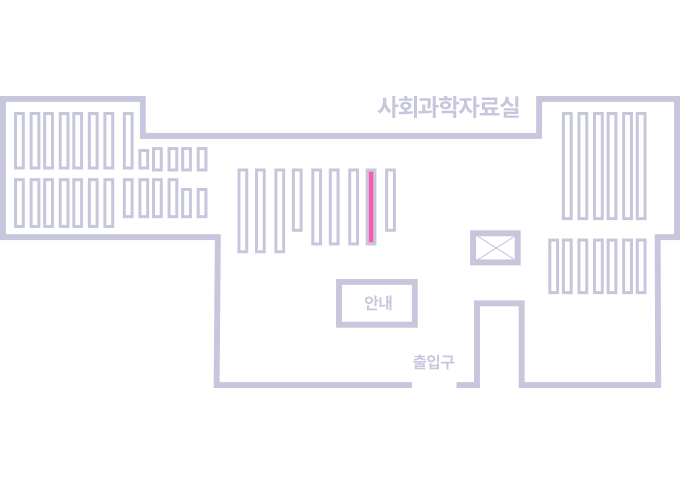

도서위치안내: 정기간행물실(524호) / 서가번호: 국내18

2021년 이전 정기간행물은 온라인 신청(원문 구축 자료는 원문 이용)

우편복사 목록담기를 완료하였습니다.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

저장 되었습니다.