권호기사보기

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 대표형(전거형, Authority) | 생물정보 | 이형(異形, Variant) | 소속 | 직위 | 직업 | 활동분야 | 주기 | 서지 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 연구/단체명을 입력해주세요. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

* 주제를 선택하시면 검색 상세로 이동합니다.

本論文は『源氏物語』の登場人物の末摘花を中心に物語作者の複眼的視点が光源氏の造型にいかに関わるかを考察したものである。 取り柄のない醜女として登場する末摘花は末摘花巻では否定的に評価される。源氏の失望感として現れたその否定的評価は単に空蝉に劣る外見や内面のみではなく、貧しい没落貴族でありながらも変化を嫌う生き方にも及んでいる。ところが、蓬生巻では生き方を変えずに貧しさの中で源氏を待ち続けた末摘花が肯定的に評価される。このような末摘花に対する評価の変化は語りの視点が変わった結果でもあるが、源氏が彼女を褒め称えて二条東院に引き取った内容を考えれば問題を語りの視点変化だけに限定できないように思われる。蓬生巻が源氏の須磨・明石退去を背景にすることを視野に入れれば、末摘花に対する肯定的な評価には須磨・明石退去の際に源氏が味わった経験が影響を及ぼしているようである。桐壺院の死後、須磨・明石退去を経るうちに源氏が人々の心変わりを目睹したために末摘花の変わらない心を高く評価するようになったということだが、蓬生巻にはその関係を薄弱なものにする草子地が見られる。物語作者が、不変を肯定する物語の言説における源氏の変化を価値付けにくかったために不自然な草子地を必要としたということである。ここに価値の衝突が起きた作者の複眼的視点が確認できる。 物語作者の視点は源氏に内在化して現れることもあるが、時には源氏を客体化することもある。前者の例は末摘花巻を挙げることができ、後者は玉鬘十帖で末摘花の古風な和歌詠みを非難する源氏の様子から確認できる。末摘花の変わらない古風な歌詠みを非難する源氏の様子は歌論に対する見解としても解し得るが、玉鬘に対して母の夕顔の時に変わらない愛情を訴える源氏の様子に照応して考えれば、源氏の変わらない好色を非難する物語作者の声のようにも思われる。源氏物語を短篇として局所的に読む時と一本の長編として読む時は、作者の複眼的視点が源氏を物語の価値を規定する存在にも物語の価値に反する存在にも造型する。末摘花という人物はそのような読書のためのライドラインを提示する存在なのである。

This paper considers how the stereoscopic viewpoint of the author of The tale of Genji is related to the Genji’s character molding. And the consideration will start with Suetsumuhana, a female character who has oppositional evaluation.

Suetsumuhana is considered a negative figure in “The Saffron-Flower” chapter. The negative perception that Genji’s disappointment shows not only her inferior appearance and inner self, but also her life attitude that seems to refuse to escape poverty. However, in the “The Palace in the Tangled Woods” chapter, Suetsumuhana’s refusal to escape poverty is positively evaluated. This change of evaluation is due to not only a change in the viewpoint of a narrative but also Genji’s change. While experiencing Kiritsubon’s death and the eviction of Suma and Akashi, Genji saw people changing according to the times. It makes Genji look at Setsumuhana positively. However, there are signs of negating such a relationship in “The Palace in the Tangled Woods” chapter. The narrative author replaces the unnatural sausage instead of adding value to the changes in Genji in a statement affirming the unchanged appearance. Here you can see the author’s point of view of conflict of value.

The viewpoint of the narrative is sometimes indicated by the Genji, but sometimes the Genji is objectified. An example of the former is “The Saffron-Flower” chapter. Another example of the latter is the criticism to Suetsumuhana who practiced an old-style Waka in Tamakazura-jujo. Genji, who criticizes the old-style Waka, may be a force of opinion about Waka. However, if you think about Genji’s constant amorous personality, you can take it as a rebuke to Genji’s unalterable personality. When we read a chapter of The tale of Genji as a short story, and as we read The tale of Genji as a long narrative Genji differentiates hemself from the stereoscopic viewpoint of the author. The character, Siethmuhana, presents guidelines for such reading.| 번호 | 참고문헌 | 국회도서관 소장유무 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 呉羽長(1984.3) 「「蓬生」巻草子地試解」 「日本文学」33(3) 日本文学協会 pp.72-76 | 미소장 |

| 2 | 坂本共展(1993) 「源氏と末摘花」 「源氏物語作中人物論」 勉誠社 pp.215-227 | 미소장 |

| 3 | 島内景二(1993.10) 「嫉妬する末摘花」 「国文学」38-11 學燈社 p.97 | 미소장 |

| 4 | 鈴木日出男(1991.4) 「夕顔と末摘花―「源氏物語」の古代的構造についての断章―」 「文学」2-2 岩波書店 pp.139-151 | 미소장 |

| 5 | 土方洋一(2013) 「「源氏物語」の巻々と語りの方法―蓬生巻の語りを中心に―」 「物語の言語―時代を超えて―」 青簡舎 pp.73-92 | 미소장 |

| 6 | 藤原克己(1979.6) 「古風なる人々」 「むらさき」16 武蔵野書院 pp.25-33 | 미소장 |

| 7 | 藤原克己(1993) 「源氏物語と白氏文集―末摘花巻の「重賦」引用を手がかりに―」 「和漢比較叢書第十二巻 源氏物語と漢文学」 汲古書院 pp.103-119 | 미소장 |

| 8 | 増田繁夫(1980) 「品定まれる人、空蝉」 「講座源氏物語の世界<第一集>」有裴閣 pp.172-184 | 미소장 |

| 9 | 松田成穂(1983.3) 「末摘花の思想―源氏物語における兼済への志―」 「山手国文論攷」5 神戸山手女子短期大学国文学科 pp.1-25 | 미소장 |

| 10 | 三谷邦明(1989) 「源氏物語の方法―ロマンからヌヴェルへあるいは虚構と時間ㅡ」 「物語の方法」 有精堂 pp.5-40 | 미소장 |

| 11 | 森一郎(1969) 「源氏物語における人物造形の方法と主題との関連」 「源氏物語の方法」 桜楓社 pp.193-217 | 미소장 |

| 12 | 山本利達(1985) 「作者の人間理解―末摘花を中心に―」 「源氏物語の探究 第10輯」 風間書房 p.109 | 미소장 |

| 13 | 吉田幹生(2015) 「蓬生巻の末摘花」 「日本古代恋愛文学史」 笠間書院 pp.330-355 | 미소장 |

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

| *전화번호 | ※ '-' 없이 휴대폰번호를 입력하세요 |

|---|

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 번호 | 발행일자 | 권호명 | 제본정보 | 자료실 | 원문 | 신청 페이지 |

|---|

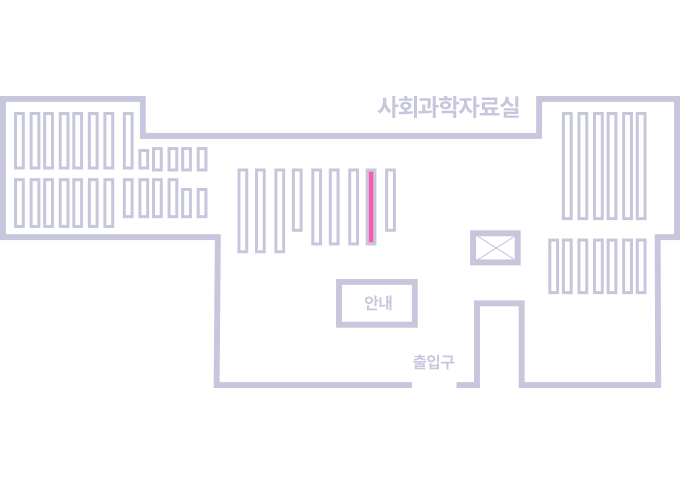

도서위치안내: 정기간행물실(524호) / 서가번호: 대학02

2021년 이전 정기간행물은 온라인 신청(원문 구축 자료는 원문 이용)

우편복사 목록담기를 완료하였습니다.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

저장 되었습니다.