권호기사보기

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 대표형(전거형, Authority) | 생물정보 | 이형(異形, Variant) | 소속 | 직위 | 직업 | 활동분야 | 주기 | 서지 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 연구/단체명을 입력해주세요. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

* 주제를 선택하시면 검색 상세로 이동합니다.

This article examines the literary predecessors of contemporary South Korean wealth inequality critiques, arguing for the inseparability of such parables, particularly Lee Chang-dong's (Yi Ch’angdong 李滄東) Burning (Pŏning버닝2018), from a contested tradition of writing about generational poverty and discrimination. Focusing on literary representations of the Cold War-era guilt- by-association system or yŏnjwaje 緣坐制, it draws out the relationship between the anti-communist epistemologies of authoritarian regimes, the right-wing literature of Yi Munyŏl 李文烈, and the leftist-nationalist allegories of Lee, a novelist before his turn to film. United by what Eve Sedgwick has identified as paranoid epistemologies of exposure, these diverse forms of writing revolved around the investigation of the identity of the alleged traitor, often the spectral leftist father blamed for the socioeconomic immobility of his surviving family members. Whether reactionary or subversive, such texts affirmed the inescapability and rigidity of patrilineal inheritance, an understanding of identity and kinship that the feminist works of Ch’oe Yun 崔允 and Pak Wansŏ 朴婉緖 would challenge in two critical ways. First, these works highlighted the mutual constitution of war and domesticity, destabilizing visions of the individual or family as separate from and aligned against the social order; second, they revealed the origins of an enduring Cold War subjectivity of exposure in Korean War-era state apparatuses of identification, drawing attention to the complicity of the act of writing in the perpetuation of the sociocultural structure of the yŏnjwaje even after its legal abolition.

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 목차 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Becoming rich : economic subjectivity and the portrayal of money in modern South Korea | Anna Jungeun Lee | p. 1-28 |

|

|

| Kim Jong-il's succession campaign of the 1970s : a comparison of propaganda tracks | Fyodor Tertitskiy | p. 29-51 |

|

|

| Guilt-by-association and the wealth inequality parable : paranoia, exposure, and inheritance in South Korean literature | Thomas M. Ryan | p. 53-80 |

|

|

| From translation studies to Korean studies through a paratextual analysis of Bandi's Kobal | Seung-eun Sung, Soyoung Park, Jai-Ung Hong, Yoo-jung Kim, Hyejin Kim | p. 81-103 |

|

| 번호 | 참고문헌 | 국회도서관 소장유무 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ch’oe Yun 崔允. “Abŏji kamsi” 아버지 감시 [Father’s surveillance]. In Hwang Sŏgyŏng ŭi Han’guk myŏngdanp’yŏn 101. 7: Pyŏnhyŏk kwa miwan ŭi ch’ulbal 황석영의 한국 명단편 101. 7: 변혁과미완의 출발 [Hwang Sŏgyŏng’s notable works of Korean literature. Vol. 7, revolution and unfinished departures], edited by Hwang Sŏgyŏng, 155–190 (P’aju: Munhak Tongne, 2015). | 미소장 |

| 2 | Ch’oe Yun 崔允. Hoesaek nun saram: Ch’oe Yun taep’yo chungdan p’yŏnsŏn 회색 눈사람: 최윤 대표 중단편선 [The grey snowman: Representative short works of Ch’oe Yun]. P’aju: Munhak Tongne, 2017. | 미소장 |

| 3 | Ch’oe Yun 崔允. “Soksagim, soksagim” 속삭임, 속삭임 [Whisper, whisper]. Munhak tongne 문학동네 21, 6(11-12.1993): 184-213. | 미소장 |

| 4 | Ch’oe Yun 崔允. Yŏlse kaji ŭi irŭm ŭi kkot hyanggi 열세가지 이름의 꽃향기 [A flower scent with thirteen names]. Sŏul: Munhak kwa Chisŏngsa, 1999. | 미소장 |

| 5 | Hwang Sŏgyŏng 황석영, ed. Hwang Sŏgyŏng ŭi Han’guk myŏngdanp’yŏn 101. 7: Pyŏnhyŏk kwa miwan ŭi ch’ulbal 황석영의 한국 명단편 101. 7: 변혁과 미완의 출발 [Hwang Sŏgyŏng’s notable works of Korean literature. Vol. 7, revolution and unfinished departures]. P’aju: Munhak Tongne, 2015. | 미소장 |

| 6 | Kim Aeran 김애란. Ch’im i koinda 침이 고인다 [Mouthwatering]. Sŏul: Munhak kwa Chisŏngsa, 2007. | 미소장 |

| 7 | Kim Aeran 김애란. Pihaengun 비행운 [Vapor trails]. Sŏul: Munhak kwa Chisŏng, 2012. | 미소장 |

| 8 | Kim Isŏk 金利錫. “Hŭrŭm sok esŏ” 흐름속에서 [In the stream]. Sasanggye思想界, August 1960, 365-81. | 미소장 |

| 9 | Kim Tongnip 金東立. “Yŏndaeja” 連帶者 [Comrade]. Sasanggye 思想界, July 1960, 336–51. | 미소장 |

| 10 | Pak Min’gyu 박민규. K’asŭt’era 카스테라 [Castella]. P’aju: Munhak Tongne, 2014. | 미소장 |

| 11 | Pak Wansŏ 朴婉緖. “Pogwŏn toeji mothan kŏt tŭl ŭl wihayŏ” 복원되지 목한 것들을 위하여 [On behalf of the things that cannot be restored], Ch’angjak kwa pip’yŏng 창작과 비평 17, no. 2(1989): 149–171. | 미소장 |

| 12 | Pak Wansŏ 朴婉緖. Kinagin haru 기나긴 하루 [A long day]. P’aju: Munhak Tongne, 2012. | 미소장 |

| 13 | Yi Munyŏl 李文烈. “Kŭ sewŏl ŭn kado” 그 歲月은 가도 [Even as those times have passed]. Munhak sasang 文學思想 127 (May 1982): 141-158. | 미소장 |

| 14 | Yi Munyŏl 李文烈. “T’aorŭnŭn ch’uŏk” 타오르는 추억 [Burning memory]. Munhak sasang 文學思想 130(August 1983): 129-148. | 미소장 |

| 15 | Yi Munyŏl 李文烈. Yi Munyŏl chungdanp’yŏn chŏnjip 4: Uri tŭl ŭi ilgŭrŏjin yŏngung woe 이문열 중단편전집 4: 우리들의일그러진 영웅 외 [The complete collected short stories and novellas of Yi Munyŏl. Vol 4, our twisted hero]. Sŏul: Minŭmsa, 2016. | 미소장 |

| 16 | Yi Ch’angdong 李滄東. “Sumgyŏjin ‘punno’” 숨겨진 「분노」 [Veiled hostility]. Tonga ilbo, June 5, 1986. | 미소장 |

| 17 | Yi Ch’angdong 李滄東. Soji 燒紙 [Burning paper]. Sŏul: Munhak kwa Chisŏngsa, 1987. | 미소장 |

| 18 | Yi Ch’angdong 李滄東. Nokch’ŏn e nŭn ttong i mant’a 녹천에는 똥이 많다 [There’s a lot of shit in Nokch’ŏn]. Sŏul:Munhak kwa Chisŏngsa, 1992. | 미소장 |

| 19 | Yi Ch’angdong 李滄東. Chimnyŏm: Kil wi ŭi kil 집념: 길위의 길 [Tenacity: Paths upon paths]. Sŏul: Ch’aek Mandŭnŭn Chip, 1996. | 미소장 |

| 20 | Yi Ch’angdong 李滄東. Pŏning 버닝 [Burning]. Sŏul: CGV Arthouse, 2018. | 미소장 |

| 21 | An Miyŏng 안미영. “4.19 chikhu Sasanggye ŭi minjuhwa tamnon kwa sosŏl e chegidoen yŏnjwaje munje: Kim Tongnip ŭi ‘Yŏndaeja’ wa Kim Isŏk ŭi ‘Hŭrŭm sok e sŏ’ rŭl chungsim ŭro”4.19 직후 「사상계」의 민주화 담론과 소설에 제기된 연좌제 문제- 김동립의 「連帶者」와 김이석의「흐름속에서」를 중심으로 [Democratization discourse and novelistic treatments of the yŏnjwaje problem in Sasanggye after the April Revolution: Kim Tongnip’s “Comrade” and Kim Isŏk’s “In the Stream”]. Hyŏndae sosŏl yŏn’gu 현대소설연구 43 (2010): 315–345. | 미소장 |

| 22 | Chang Sejin 장세진. “Wŏnhan, nosŭt’aeljiŏ, kwahak: Wŏllam chisigindŭl kwa 1960-nyŏndae Pukhan hakchi ŭi sŏngnip sajŏng” 원한, 노스탤지어, 과학 - 월남 지식인들과 1960 년대 북한학지(學知)의 성립 사정 [Resentment, nostalgia, science: North Korean defector intellectuals and the conditions surrounding the establishment of North Korean research in 1960s South Korea]. Sai kan sai 사이間SAI 17 (November 2014): 141–180. | 미소장 |

| 23 | Chin Sangwŏn 진상원. “Chosŏn wangjo ŭi yŏnjwaje: Chŏngch’ibŏm huson ŭi kwagŏ ŭngsi munje rŭl chungsim ŭro” 조선왕조의 연좌제 - 정치범 후손의 과거응시 문제를 중심으로 [The Chosŏn dynasty’s guilt-by-association laws: The problem of civil service examination applications for the successors of political criminals]. Yŏksa wa kwan’gye 역사와 관계 113(December 2019): 33–77. | 미소장 |

| 24 | Cho Hoegyŏng 조회경. “Ch’oe Yun sosŏl ŭi chŏnboksŏng kwa yullisŏng ŭi kwan’gye” 최윤소설의 전복성과 윤리성의 관계 [The relationship between overturning and ethics in the novels of Ch’oe Yun]. Uri munhak yŏn’gu 우리文學硏究 56 (2017): 565–587. | 미소장 |

| 25 | Chŏng Chua 정주아. “Inyŏmjŏk chinjŏngsŏng ŭi sidae wa wŏnjoe ŭisik ŭi naemyŏn:1980-nyŏndae Yi Munyŏl sosŏl ŭi chonjae pangsik kwa t’eksŭt’ŭ ŭi ijungsŏng” 이념적진정성의 시대와 원죄의식의 내면: 1980년대 이문열 소설의 존재방식과 텍스트의 이중성 [The age of ideological authenticity and the interiority of original sin consciousness: The mode of existence of Yi Munyŏl’s 1980s novels and the duplicity of the text]. Minjok munhaksa yŏn’gu 민족문학사연구 54 (2014): 7–33. | 미소장 |

| 26 | Chŏng Hasŏng 정하성. “Munje insik kanghan Yi Ch’angdong changgwan ‘chaebŏl hoejang iltaegi chipp’il iyu nŭn?’” 문제의식 강한 이창동 장관 “재벌회장 일대기 집필한 이유는?” [Critically aware Minister Yi Ch’angdong: “What was the reason he published a biography of a chaebŏl chairman?”]. Iryo Sŏul 일요서울, July 3, 2003. http://www.ilyoseoul.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=1871. | 미소장 |

| 27 | Chŏng Kwari 정과리. “Nanal ŭi chŏnjaeng: Ilsang ŭi yŏksa mandŭlgi” 나날의 전쟁: 이상의 역사만들기 [Everyday War: The Making of the History of Everyday Life]. Commentary on Yŏlse kaji ŭi irŭm ŭi kkot hyanggi 열세 가지의 이름의 꽃향기, by Ch’oe Yun 최윤, 292-312. (Sŏul: Munhak kwa Chisŏngsa, 1999). | 미소장 |

| 28 | Ch’a Miryŏng 차미령. “Han’guk Chŏnjaeng kwa sinwŏn chŭngmyŏng changch’i ŭi kiwŏn: Pak Wansŏ sosŏl e nat’anan chugwŏn ŭi munje” 한국 전쟁과 신원 증명 장치의 기원 - 박완서 소설에나타난 주권의 문제 [The Korean War and the origins of identification apparatuses: The problem of sovereignty in Pak Wansŏ’s novels]. Kubo hakpo 구보학보 18 (2018): 449–480. | 미소장 |

| 29 | Freud, Sigmund. Three Case Histories. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996. | 미소장 |

| 30 | Hŏ Ŭn 허은. “‘Mit ŭro put’ŏ ŭi naengjŏn,’ kŭ yonswae wa hwallyu: 1957–1963-nyŏn Miguk ŭi Tong Asia naengjŏn chŏllyak chŏnhwan kwa Han’guk kunbu ŭi ‘taemin hwaldong(civic action)’ sihaeng” ‘밑으로부터의 냉전,’ 그 연쇄와 환류 – 1957–1963년 미국의 동아시아 냉전전략과 한국 군부의 ‘대민활동(civic action)’ 시행 [Connections and returns of the “Cold War from below”: U.S. Cold War strategic shifts in East Asia and the South Korean military government’s implementation of military civic actions, 1957–1963]. Yŏksa munje yŏn’gu 역사문제연구 23, no. 1 (April 2019): 417–456. | 미소장 |

| 31 | Hughes, Theodore H. Literature and Film in Cold War South Korea: Freedom’s Frontier. New York:Columbia University Press, 2012. | 미소장 |

| 32 | Han Honggu 한홍구. “Irŏbŏrin abŏji tŭl ŭl wihan hŏnjuga – Kim Sŏngdong Hyŏndaesa arirang, noksaek p’yŏngnon 2010” 잃어버린 아버지들을 위한 헌주가 -김성동 「현대사 아리랑」, 녹색평론2010 [An elegy for lost fathers: On Kim Sŏngdong, An Arirang for Modern History]. Ch’angjak kwa pip’yŏng 창작과 비평 39, no. 2 (June 2011): 398–401. | 미소장 |

| 33 | Hwang Pyŏngju 황병주. “Yusin ch’ejegi p’yŏngdŭng-pulp’yŏngdŭng ŭi munje sŏlchŏng kwa chayujuŭi” 유신체제기 평등-불평등의 문제설정과 자유주의 [Liberalism and the establishment of equality-inequality as a problem in the Yusin era]. Yŏksa munje yŏn’gu 역사문제연구 17, no. 1 (2013): 7–46. | 미소장 |

| 34 | Hwang Togyŏng 황도경. Uri sidae ŭi yŏsŏng chakka 우리 시대의 여성 작가 [Women writers of our era]. Sŏul: Munhak kwa Chisŏngsa, 1999. | 미소장 |

| 35 | Im Ugi 임우기. “80-nyŏndae pundan sosŏl ŭi saeroun chŏn’gae: Taebaek sanmaek kwa Kyŏul koltchagi e taehayŏ” 80년대 분단소설의 새로운 전개 「태백산맥」과 「겨울 골짜기」에 대하여 [New developments in division novels of the 1980s: On The Taebaek Mountains and A Winter Valley]. Munhak kwa sahoe 문학과사회 1, no. 1 (February 1988): 49–71. | 미소장 |

| 36 | Kang Chunman 강준만. Hŭisaengyang kwa choe ŭisik: Taehan Min’guk pan’gong ŭi yŏksa 희생양과죄의식: 대한민국 반공의 역사 [Scapegoat and guilty conscience: The history of South Korean anti-communism]. Sŏul: Kaema Kowŏn, 2004. | 미소장 |

| 37 | Kim Chaeung 김재웅. “Yŏnjwaje wa ch’ulsin sŏngbun ŭi kyujŏngnyŏk ŭl t’onghae pon haebang hu Pukhan ŭi kajok chŏngch’aek” 연좌제와 출신성분의 규정력을 통해 본 해방후 북한의 가족정책 [Post-liberation North Korean family policies viewed through the influence of guilt-by-association laws and family classes]. Tongbang hakchi 東方學志 187(2019): 313–341. | 미소장 |

| 38 | Kim Chinhwan 김진환. “Ppalch’isan, yŏksa ŭi kyŏngnang e sŏn saram” 빨치산, 역사의 격랑에선 사람 [The partisan, a person standing on the raging waves of history]. Yŏksa pip’yŏng 역사비평 94 (February 2011): 298–328. | 미소장 |

| 39 | Kim, Dong-Choon. The Unending Korean War: A Social History. Larkspur, CA: Tamal Vista Publications, 2009. | 미소장 |

| 40 | Kim, Elaine H., and Chungmoo Choi, eds. Dangerous Women: Gender and Korean Nationalism. New York: Routledge, 1998. | 미소장 |

| 41 | Kim Hyŏnju 김현주. “Kŭmsujŏ … taehaksaeng, olhae ŭi sinjoŏ ro kkoba: ‘Hel Chosŏn’‘Np’osedae’ ka twiiŏ” 금수저 … 대학생, 올해의 신조어로 꼬바: ‘헬조선’ ‘N포세대’가 뒤이어 [Gold spoons, chosen by university students as this year’s neologism: Hell Chosŏn and N-p’o generation follow close behind]. Kukche sinmun 국제신문, December 24, 2015. http://www. kookje.co.kr/news2011/asp/newsbody.asp?code=0300&key=20151225.22006192310. | 미소장 |

| 42 | Kim Myŏnghun 김명훈. “’87-nyŏn ch’eje’ wa chiyŏndoen chŏnhyang ŭi wansu:1980–90-nyŏndae Kim Wŏnil, Yi Mun’gu, Yi Munyŏl sosŏl ŭi pyŏnhwa rŭl chungsim ŭro” ‘87년 체제’와 지연된 전향의 완수: 1980–90년대 김원일, 이문구, 이문열 소설의 변화를중심으로 [The 1987 system and the completion of a postponed conversion: Changes in the novels of Kim Wŏnil, Yi Mun’gu, and Yi Munyŏl in the 1980s and 1990s]. Sanghŏhakpo 상허학보 60 (October 2020): 219–264. | 미소장 |

| 43 | Kim Ŭnjae 김은재, and Kim Sŏngch’ŏn 김성천. “Yŏnjwaje p’ihaejadŭl ŭi kukka p’ongnyŏk kyŏnghŏm e taehan sarye yŏn’gu: Kkŭt ŏpnŭn tomangja ro saranamgi” 연좌제 피해자들의국가폭력 경험에 대한 사례연구 - 끝없는 도망자로 살아남기 [Case studies of yŏnjwaje victims’experience of state violence: Survival as eternal fugitives]. Pip’an sahoe chŏngch’aek 비판사회정책 51 (2016): 244–291. | 미소장 |

| 44 | Ko Minjŏng 고민정. “Chosŏn hugi yŏnjwaje unyŏng ŭl t’onghae pon p’agye ŭi yangsang kwa kagye kyesŭng” 조선후기 연좌제 운영을 통해 본 罷繼의 양상과 가계계승 [Viewing the dissolution of adoptive care and household succession through late Chosŏn era operation of guilt-by-association laws]. Sahak yŏn’gu 사학연구 124 (December 2016): 53–86. | 미소장 |

| 45 | Kwon, Heonik. After the Korean War: An Intimate History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020. | 미소장 |

| 46 | Lacan, Jacques. Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English. Translated by Bruce Fink. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2007. | 미소장 |

| 47 | Lee, Jin-Kyung. “National History and Domestic Spaces: Secret Lives of Girls and Women in 1950s South Korea in O Chông-Hûi’s ‘The Garden of Childhood’ and ‘The Chinese Street.’” Journal of Korean Studies 9, no. 1 (2004): 61–95. | 미소장 |

| 48 | Lee, Jin-Kyung. Service Economies: Militarism, Sex Work, and Migrant Labor in South Korea. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2010. | 미소장 |

| 49 | Lee, Peter H., ed. A History of Korean Literature. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003. | 미소장 |

| 50 | Pak Chinyŏng 박진영. “1970-nyŏndae sosŏl e nat’anan kŏjugwŏn ŭi munje wa konggan ŭi pulli: Cho Sehŭi·Yun Hŭnggil sosŏl ŭl chungsim ŭro” 1970년대 소설에 나타난 거주권의문제와 공간의 분리 - 조세희·윤흥길 소설을 중심으로 [Spatial segregation and the problem of the right of residence in 1970s literature: The novels of Cho Sehŭi and Yun Hŭnggil]. Yŏllin chŏngsin inmunhak yŏn’gu 열린정신 인문학 연구 17, no. 1 (April 2016): 239–258. | 미소장 |

| 51 | Park, Sunyoung. The Proletarian Wave: Literature and Leftist Culture in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center, 2015. | 미소장 |

| 52 | Ryu, Youngju. Writers of the Winter Republic: Literature and Resistance in Park Chung Hee’s Korea. Honolulu: University of Hawai‛i Press, 2016. | 미소장 |

| 53 | Sass, Louis A. “Schreber’s Panopticism: Psychosis and the Modern Soul.” Social Research 54, no. 1 (Spring 1987): 101–147. | 미소장 |

| 54 | Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003. | 미소장 |

| 55 | Tambling, Jeremy. Literature and Psychoanalysis. Manchester University Press, 2013. | 미소장 |

| 56 | Yi Ch’ŏrho 이철호. “Changch’i rosŏ ŭi yŏnjwaje – 1980-nyŏndae Yi Munyŏl ŭi ch’ogi tanp’yŏn kwa ‘chungsanch’ŭng’ p’yosang” 장치(dispositif)로서의 연좌제 – 1980년대이문열의 초기 단편과 ‘중산층’ 표상[Yŏnjwaje as document: Yi Munyŏl’s early short stories and representations of the middle class]. Hyŏndae munhak ŭi yŏn’gu 현대문학의 연구 56(2015): 369-396. | 미소장 |

| 57 | Yi Ch’ŏrho 이철호. “Chungsan ch’ŭng kwa yŏnjwaje: Yi Munyŏl ŭi ch’ogi tanp’yŏn ŭl chungsim ŭro”중산층과 연좌제 - 이문열의 초기 단편을 중심으로 [The middle class and guilt by association:Yi Munyŏl’s early short stories]. Han’guk hyŏndae munhakhoe haksul palp’yohoe charyojip 한국현대문학회 학술발표회자료집 (August 2014): 415–422. | 미소장 |

| 58 | Yi Hyeryŏng 李惠鈴. “Pak Wansŏ ŭi 1980-nyŏndae – ppalgaengi, undonggwŏn, sahoejuŭi(cha)ŭi chŏrhap” 박완서의 1980년대- 빨갱이, 운동권, 사회주의(자)의 절합 [Pak Wansŏ’s 1980s:Articulating communists, activists, and socialists]. Kukje ŏmun 국제어문 79 (2018): 357–384. | 미소장 |

| 59 | Yi Hyeryŏng 李惠鈴. “Ppalch’isan kwa ch’inilp’a: Ŏttŏn yŏksa hyŏngsang ŭi chongŏn kwa mirae e taehayŏ”빨치산과 친일파 – 어떤 역사 형상의 종언과 미래에 대하여 [The partisan and the collaborator:On the end and future of figures of history]. Taedong munhwa yŏn’gu 大東文化硏究 100(2017): 445–475. | 미소장 |

| 60 | Yi Miyŏng 이미영. “Nuga kyoyang sosŏl ŭl norae hanŭn ka: Kyoyang chuch’e ŭi namsŏng(sŏng)net’ŭwŏkŭ wa Yi Munyŏl ŭi 1980 nyŏndae t’eksŭt’ŭ” 누가 교양소설을 노래하는가 - 교양주체의 남성(성) 네트워크와 이문열의 1980년대 텍스트 [Who sings the bildungsroman? Networks of developmental subjects and Yi Munyŏl’s works of the 1980s]. Sanghŏ hakpo 상허학보 56 (2019): 481–524. | 미소장 |

| 61 | Yi Naegwan 이내관. “Yi Ch’angdong pundan sosŏl e nat’anan ‘abŏji’ ŭi ŭimi” 이창동 분단소설에나타난 ‘아버지’의 의미 [The meaning of the father in the division novels of Yi Ch’angdong]. Pip’yŏng munhak 비평문학 56 (June 2015): 159–183. | 미소장 |

| 62 | Yi Pongbŏm 이봉범. “Naengjŏn kwa wŏlbuk, (nap)wŏlbuk ŭije ŭi munhwa chŏngch’i” 냉전과월북, (납)월북 의제의 문화정치 [The Cold War and defection: The cultural politics of defection (kidnapping)]. Yŏksa munje yŏn’gu 역사문제연구 21, no. 1 (2017): 229–294. | 미소장 |

| 63 | Yi Sŏnmi 이선미. “‘Puyŏk (hyŏmŭi)ja’ sŏsa wa naengjŏn ŭi maŭm: 1970-nyŏndae Pak Wansŏsosŏl ŭi ‘ppalgaengi’ tamnon kwa kŭ sahoejŏk ŭimi” ‘부역(혐의)자’ 서사와 냉전의 마음:1970년대 박완서 소설의 ‘빨갱이’ 담론과 그 사회적 의미 [The (suspected) traitor narrative and the mind of the Cold War: “Communist” discourse and its social meaning in the 1970s novels of Pak Wansŏ]. Han’guk munhak yŏn’gu 한국문학연구 65 (April 2021): 345–378. | 미소장 |

| 64 | Yŏ Hyŏnch’ŏl 여현철. “Kukka p’ongnyŏk e ŭihan yŏnjwaje p’ihae sarye punsŏk: Chŏns nappukja kajok ŭi p’ihae kyŏnghŏm ŭl chungsim ŭro” 국가폭력에 의한 연좌제 피해 사례분석 - 전시 납북자 가족의 피해 경험을 중심으로 [An analysis of case studies of victims of guilt-by-association practices through state violence: The experiences of the families of those kidnapped by the North during the war]. Kukje chŏngch’i yŏn’gu 국제정치연구 21, no. 1 (June 2018): 171–191. | 미소장 |

| 65 | Žižek, Slavoj. “The Seven Veils of Paranoia, or, Why Does the Paranoiac Need Two Fathers?”Constellations 3, no. 2 (1996): 139–56. | 미소장 |

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

| *전화번호 | ※ '-' 없이 휴대폰번호를 입력하세요 |

|---|

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 번호 | 발행일자 | 권호명 | 제본정보 | 자료실 | 원문 | 신청 페이지 |

|---|

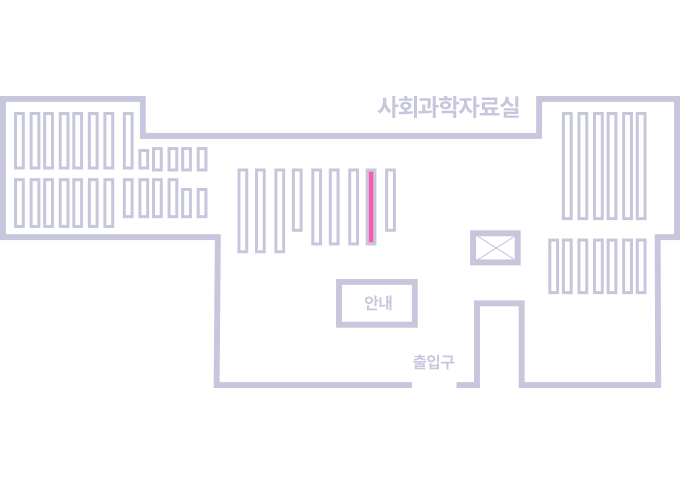

도서위치안내: 정기간행물실(524호) / 서가번호: 대학01

2021년 이전 정기간행물은 온라인 신청(원문 구축 자료는 원문 이용)

우편복사 목록담기를 완료하였습니다.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

저장 되었습니다.