권호기사보기

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 대표형(전거형, Authority) | 생물정보 | 이형(異形, Variant) | 소속 | 직위 | 직업 | 활동분야 | 주기 | 서지 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 연구/단체명을 입력해주세요. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

* 주제를 선택하시면 검색 상세로 이동합니다.

나도향이 톨스토이 민화집 『사람은 무엇으로 사느냐』를 번역한 사실은 오래도록 문학사에서 망각되거나 간과된 사실이다. 특별한 공통점을 찾기 힘든 둘이었기에 도향의 민화 번역은 그의 이력에서 부차화됐던 듯하다. 그러나 도향이 톨스토이와 반(反) 기독교를 교집합으로 공명하면서 대중에게 영적인 메시지를 전하는데 고심한 점에서, 그의 번역은 의식적이고 주체적인 선택의 결과였다.

연구사 차원에서 저본 및 번역 텍스트에 대한 고구가 전무했기에, 이 연구는 우선 저본을 발굴하고 저본의 성격과 번역상 특징을 밝히는 실증적인 작업에서 출발했다. 그 결과, 1) 저본이 노보리 쇼무와 쿠보 마사오가 공역한 『人は何によつて生くるか』(1921) 그리고 오오타 쇼오이치 역의 「愛ある所に神あり」(1929)의 전신이었을 미확인 일역텍스트였다는 점, 2) 이것들이 러시아 원문을 직역했거나 당시는 물론 지금도 대중적 수요가 있는 영역본을 저본으로 한 완역이었다는 점, 3) 번역 과정에서 도향이 부분적인 자국화역을 시도하고 가독성을 제고하며 문학성을 살리는 변형을 가한 점 등을 밝혀냈다.

톨스토이 민화를 번역하게 된 동기로서 도향의 반기독교적 문제의식이 큰 자리를 차지하고 있었다는 점도 이 글이 밝히려 한 요지 가운데 하나다. 도향이 기독교를 비판적으로 수용하게 된 매개체로서 톨스토이라는 교회의 ‘이단아’가 존재했는데, 도향은 제도로서의 교회를 부정하고 사랑과 동정의 윤리를 내세운 톨스토이와 작품 차원에서 여러모로 닮은 구석을 내비치고 있었다. 그러나 톨스토이에 동의할 수 없는 부분이 도향에게 또한 존재했는데, 악에 저항하지 말라는 무저항주의가 그것이다. 도향의 거리감은 「초」를 번역하며 도덕적 당위성과 종교적 색채를 덜어낸 점, 그리고 번역 이후 달라진 자신의 창작 행보에서 확인됐다. 「벙어리 삼룡이」, 「미정고 장편」, 「화염에 쌓인 원한」은 정열적인 주체의 투쟁/저항을 통해 세상의 악과 싸우려는 도향만의 문제의식을 보여주는 텍스트였다.

It has long been forgotten or overlooked in the literary history that Na Do-hyang translated Tolstoy’s folktales, What People Live By. It seems that this translation was regarded as secondary in his career because Do-hyang and Tolstoy had no obvious common ground. However it can be said that his translation of these folktales was the result of a conscious choice, in that Do-hyang was devoted to transmitting a spiritual message to the public while intersetcing with Tolstoy’s works through the latter’s anti-Christian themes.Since there has been no investigation of Do-hyang’s translation texts and its original source texts in the academic world, this study first started as an empirical work which set out to discover the original texts and to analyze their features and aspects of their translation. As a result it was revealed that 1) the original texts were 『人は何によつて生くるか』(1921) which was the collaborative translation of Shomu Nobori and Masao Kubo, and an unavailable Japanese text which was the predecessor of 「愛ある所に神あり」(Shoichi Ota trans., 1929); 2) they were complete translations which were translated directly from the original Russian text or from English texts that were popular both at that time and are also popular now; 3) Do-hyang partially tried to ’domesticate’ the texts, attempted to improve the readers’ readability, and transformed them in ways that enhance their expressive power through the translation process.One of the points that this article aimed to clarify was that Do-hyang’s anti-Christian attitude was a significant part of the motivation for translating Tolstoy’s folktales. His critical acceptance of Christianity was based on the ‘heresy’ of the Church, Tolstoy who denied the church as an institution and presented an ethics of love and sympathy, and Do-hyang’s works showed similarities with his in this way. However Do-hyang could not agree with Tolstoy’s stance on ‘non-resistance’ to evil. Do-hyang’s sense of distance from this perspective was verified in his creations after his translation of Tolstoy, as he tried to reduce the space of moral justifications and religious dimensions in translating “Candle”. “Mute Samryong-i”, “Rough Draft Short Stories” and “The Wrath in the Fire” are the texts that show Do-hyang’s own critical frame of mind in relation to fighting the evil of the world through the passionate subject’s struggle and resistance.*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

| *전화번호 | ※ '-' 없이 휴대폰번호를 입력하세요 |

|---|

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 번호 | 발행일자 | 권호명 | 제본정보 | 자료실 | 원문 | 신청 페이지 |

|---|

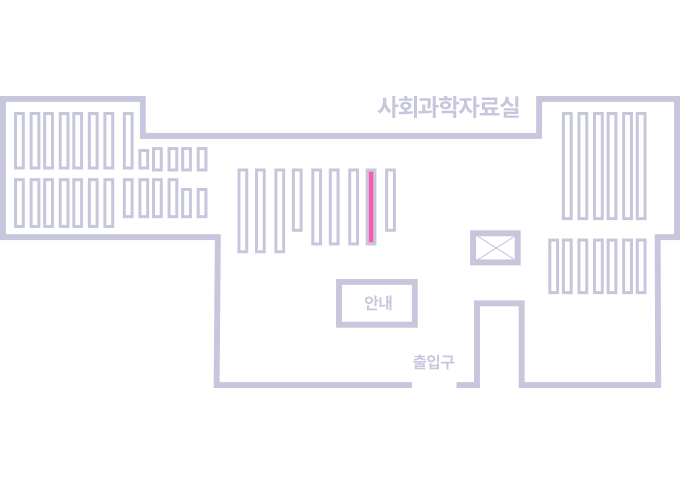

도서위치안내: / 서가번호:

우편복사 목록담기를 완료하였습니다.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

저장 되었습니다.