권호기사보기

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 대표형(전거형, Authority) | 생물정보 | 이형(異形, Variant) | 소속 | 직위 | 직업 | 활동분야 | 주기 | 서지 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 연구/단체명을 입력해주세요. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

* 주제를 선택하시면 검색 상세로 이동합니다.

영문목차

List of Figures=xi

List of Tables=xiv

List of Boxes=xvii

List of Contributors=xviii

Introduction / By Tito Boeri=1

Part I. Understanding Highly Skilled Migration in Developed Countries : The Upcoming Battle for Brains / By Herbert Brücker ; Simone Bertoli ; Giovanni Facchini ; Anna Maria Mayda ; Giovanni Peri=15

Introduction=17

1. Selecting the Highly Skilled : An Overview of Current Policy Approaches=23

1.1. A classification of skill-selective immigration policies=24

1.2. Skill-selective immigration policies in traditional immigration countries=25

1.3. Skill-selective immigration policies at the EU level=29

1.4. Skill-selective immigration policies in a group of EU member countries=30

1.5. Present and future policies to attract highly skilled immigrants : evidence based on UN data=34

1.6. Conclusions=35

2. Global Trends in Highly Skilled Immigration=36

2.1. Highly skilled immigrants in the OECD=37

2.2. How large is the global pool of highly skilled labour?=47

2.3. Looking at the top of the skill distribution=50

2.4. The competition for foreign students=54

2.5. How do highly skilled immigrants assimilate into host labour markets?=60

2.6. Conclusions=64

3. The Determinants of Highly Skilled Migration : Evidence from OECD Countries 1980-2005=66

3.1. The empirical model=68

3.2. Data=71

3.3. Regression results=81

3.4. Discussion and conclusions=93

4. The Effects of Brain Gain on Growth, Investment, and Employment : Evidence from OECD Countries, 1980-2005=106

4.1. A production function framework=108

4.2. Data on employment, capital intensity, and productivity=111

4.3. The effects of immigration and brain gain=112

4.4. The effects of immigration and brain gain in bad economic times=121

4.5. Conclusions=124

5. The Political Economy of Skilled Immigration=127

5.1. The elements of a political economy model of immigration policy=128

5.2. Understanding individual attitudes towards skilled migrants=130

5.3. From individual preferences to immigration policy=144

5.4. Empirical assessment=149

5.5. Conclusions=156

6. Can the Battle for Brains turn into a Tragedy of the Commons?=169

6.1. International mobility of labour and human capital formation at origin=172

6.2. A model of the Battle for Brains=175

6.3. Conclusions=182

7. Conclusions=184

7.1. Incremental shifts toward more skill-selective immigration policies=184

7.2. Skilled migration flows are concentrated in a few countries characterized by skill-selective immigration polices=185

7.3. The wage premium for education and skill-selective immigration policies is an important driver of skilled migration=186

7.4. Immigration and the brain gain are beneficial for receiving economies=186

7.5. How do immigration and the brain gain affect economies in the downturn of the business cycle?=187

7.6. Why do skill-selective immigration policies not find more support?=187

7.7. Will the policy equilibrium shift towards more skill-selective immigration policies?=188

7.8. Can the upcoming skill contest produce losers among destination and sending countries?=188

References=190

Comments=199

Franco Peracchi=199

Sascha Becker=203

Part II. Quantifying the Impact of Highly Skilled Emigration on Developing Countries / By Frédéric Docquier ; Hillel Rapoport=209

Introduction=211

8. The Size of the Brain Drain=213

8.1. Extensive measures of the brain drain=214

8.2. Magnitude of 'South-South' migration=220

8.3. Accounting for country of training=223

8.4. The brain drain of scientists and health professionals=225

9. Theory, Evidence, and Implications=233

9.1. Endogenizing economic performances=234

9.2. The human capital channel=238

9.3. The screening-selection channel=250

9.4. The productivity channel=254

9.5. The institutional channel=261

9.6. Summing up : brain drain and economic performance=267

9.7. The transfer channel=272

10. Policy Issues=277

10.1. Implications for education (and other) policies in sending countries=278

10.2. Immigration (and emigration) policy=281

10.3. Taxation policy : the case for a Bhagwati tax=284

10.4. Migration flows and immigration policy in times of crisis=287

11. Conclusion=290

References=291

Comments=297

Antonio Spilimbergo=297

Alessandra Venturini=302

Index=309

List of Boxes

5.1. The political economy of international factor mobility=146

9.1. Predicting GDP per capita=237

9.2. Brain drain and human capital accumulation=240

9.3. Brain drain and the screening channel=253

9.4. Brain drain and total factor productivity=256

9.5. Brain drain and remittances=274

2.1. Foreign-born population with tertiary education attainment in selected destination countries, 1975-2000.=41

2.2. Share of source countries in highly skilled immigrant stock by income level, 1975-2000.=46

2.3. 25+ population with tertiary educational attainment, countries classified by income, 1975-2000.=49

2.4. Participation of foreigners in tertiary education and advanced education programmes in the OECD-27, 1998-2006.=55

2.5. Annual wage incomes of PhD graduates in USA, 2000.=62

2.6. Annual wage incomes of PhD graduates in Canada, 2001.=62

2.7. Annual wage incomes of highly skilled professionals(ISCO 2) in USA, 2000.=63

2.8. Annual wage incomes of highly skilled professionals(ISCO 2) in Canada, 2001.=63

3.1. Annual inflows of immigrants into the OECD-14 as percentage of population, 1980-2005.=72

3.2. Average composition of immigration flows into the OECD-14 by education, 1980-2005.=73

3.3. Average behaviour of the Immigration laws : 14 OECD countries, population weighted.=76

A3.1. Immigration rates 1980-2005.=97

5.1. Determination of immigration policy.=129

5.2. The tax adjustment model.=132

5.3. The benefit adjustment model.=132

5.4. The impact of individual attitudes towards skilled immigrants(2002-2003) on skilled migration policies (2007).=150

5.5. The impact of individual attitudes towards skilled immigrants(2002-2003) on skilled migration policies (2007).=151

5.6. Top 10 spenders for immigration, 2001-2005.=153

5.7. Top 10 sectors with the highest number of visas, 2001-2005.=153

5.8. Scatterplot―lobbying expenditures for immigration and number of H1B visas.=154

5.9. Scatterplot―membership rates in unions and employee professional associations and n umber of H1B visas.=155

A5.1. Per capita GDP and skill composition of natives relative to immigrants, 1995.=162

A5.2. Per capita GDP and skill composition of natives relative to immigrants, 2003.=162

6.1. Aggregate scale of migration and migrants' education.=181

8.1. Highly skilled emigration rates in 2000.=217

8.2. Change in highly skilled emigration rates(1990-to-2000 ratio).=218

8.3. Skill ratio of emigration rates in 2000(high-to-low ratio).=219

8.4. Ratio of extended-to-OECD highly skilled emigration rates in 2000.=221

8.5. Impact of non-OECD destinations on highly skilled emigration rates in 2000.=222

8.6. Impact of non-OECD destinations on low-skilled emigration rates in 2000.=222

8.7. Ratio of corrected-to-general brain drain rates in 2000.=223

8.8. Corrected and general brain drain rates for selected countries in 2000.=224

8.9. Physicians per 1,000 people, year 2004.=230

8.10. Medical brain drain, year 2004.=231

8.11. Change in medical brain drain, 1991-2004.=232

9.1. Costs of the brain drain under the traditional view(as a percentage of the observed GDP per capita) as a function of the highly skilled emigration rate.=238

9.2. Short-run effect of highly skilled emigration rate(X-axis) on the proportion of educated residents as percentage points(Y-axis).=248

9.3. Short-run effect of highly skilled emigration rate(X-axis) on the proportion of educated residents as percentage points(Y-axis).=249

9.4. Brain drain and the relative ability of highly skilled residents.=254

9.5. Long-run TFP response(Lodigiani's specification).=260

9.6. Long-run TFP response(Lucas' specification).=261

9.7. Brain drain and the risk premium on returns to capital.=267

9.8. Short-run brain drain cost under traditional and modern views(Scenario 1).=269

9.9. Short-run brain drain cost under traditional and modern views(Scenario 2).=270

9.10. Short-run brain drain cost under traditional and modern views(Scenario 3).=270

9.11. Short-run and long-run impacts(Scenario 2).=271

9.12. Brain drain and the between-country inequality(Scenario 2).=271

9.13. Brain drain impact GDP per capita and income per capita(Scenario 2).=275

9.14. Calibrated propensity to remit of low-skilled migrants(Y-axis) for selected recipient countries as a function of yo(X-axis).=276

10.1. Europe's(EU15) share in the brain drain from developing countries. 283

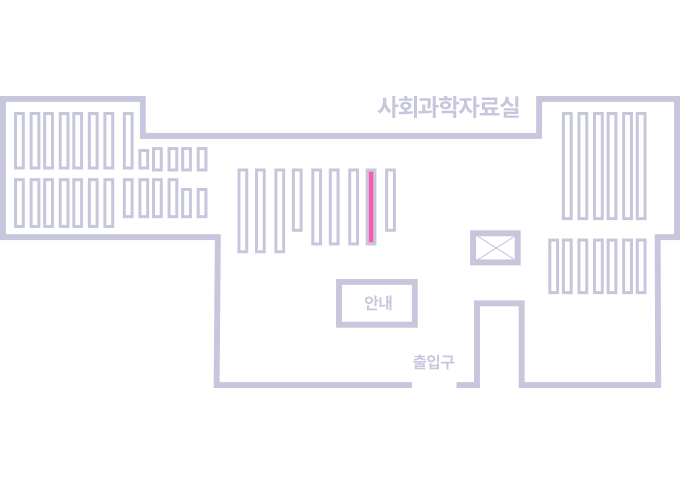

| 등록번호 | 청구기호 | 권별정보 | 자료실 | 이용여부 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0001792182 | 331.12791 -A13-1 | 서울관 서고(열람신청 후 1층 대출대) | 이용가능 |

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

| *전화번호 | ※ '-' 없이 휴대폰번호를 입력하세요 |

|---|

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 번호 | 발행일자 | 권호명 | 제본정보 | 자료실 | 원문 | 신청 페이지 |

|---|

도서위치안내: / 서가번호:

우편복사 목록담기를 완료하였습니다.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

저장 되었습니다.