권호기사보기

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 대표형(전거형, Authority) | 생물정보 | 이형(異形, Variant) | 소속 | 직위 | 직업 | 활동분야 | 주기 | 서지 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 연구/단체명을 입력해주세요. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

* 주제를 선택하시면 검색 상세로 이동합니다.

표제지

목차

제1장 서론 19

제1절 연구의 목적 19

제2절 연구범위 26

제3절 연구방법 32

제2장 집행제도의 법적 기능과 경제적·정책적 함의 35

제1절 강제집행제도의 이해 35

I. 의의 35

II. 집행방법 35

1. 강제경매와 강제관리 36

2. 강제경매의 매각방법 37

3. 금전집행의 3단계 38

III. 집행의 대상과 집행기관 39

IV. 강제경매의 신청 41

1. 신청의 방식 41

2. 강제경매와 임의경매 41

V. 강제경매 절차의 개요 46

1. 강제경매개시결정 47

2. 경매개시결정의 효력 47

3. 압류 효력의 소멸 48

VI. 부동산경매절차의 이해관계인 49

1. 이해관계인의 권리 49

2. 이해관계인의 범위 50

VII. 배당요구·매각조건·입찰의 실시 51

1. 배당요구의 종기결정 및 공고 51

2. 매각조건의 결정 52

3. 기일입찰의 실시 52

VIII. 집행으로 인한 소유권의 변동 55

1. 매각대금의 지급 55

2. 소유권이전등기의 촉탁 56

3. 부동산인도명령 56

4. 채권의 변제절차 56

제2절 집행관제도의 이해 58

I. 연혁 58

II. 집행관의 임명과 자격 60

III. 집행관제도의 실정법상 규정 61

1. 집행관 자신에 대한 규정 61

2. 집행관의 직무집행에 관한 규정 63

3. 집행관의 감독에 관한 규정 66

4. 위임자(채권자)와 채무자, 제3자에 관한 규정 67

제3절 집행제도의 기능 69

I. 권리구제의 실현 69

II. 사법절차의 보조기능 70

III. 법률집행의 기능 71

1. 민사재판의 집행 71

2. 형사재판의 집행 71

3. 가사재판의 집행 72

4. 행정재판의 집행 74

5. 집행관이 관여하는 기타 사건 76

제4절 집행제도의 경제적·정책적 함의 78

I. 현황 및 문제점 78

II. 집행제도의 정책적 함의 78

III. 집행제도의 개선방안 79

제5절 집행관제도의 바람직한 방향 81

제3장 집행관제도에 대한 비교법적 고찰 82

제1절 영국의 집행관제도 82

I. 영국의 집행관제도 일반 82

II. 영국의 집행관제도 개관 83

1. 연혁 83

2. 권한 84

3. 집행관의 임명 85

4. 집행관의 수당제 85

5. 대리집행관(Deputy Sheriff)제도 85

III. 영국의 집행관제도 특색 86

제2절 미국의 집행관제도 88

I. 미국의 집행관제도 일반 88

1. 집행관의 종류 90

2. 집행관신분의 취득과 상실 94

3. 집행관의 지위 97

II. 미국 주에서의 구체적 강제집행절차 102

1. 강제집행의 제약과 판결채권 집행의 한계 102

2. 강제집행의 시간적 제약 103

3. 채무자의 파산과 공동채무자가 존재하는 경우의 집행 108

4. 채무자가 사망한 경우의 판결 집행 110

5. 채무자 및 채무자 재산조회 방법 111

6. 채무자의 자발적인 채무 변제와 불법 채권추심 행위 116

7. 집행채권의 충족 118

8. 판결채권의 집행대상과 집행방식 121

9. 집행을 위한 집행대상의 선택과 다양한 집행방식 123

10. 판결채무 미이행에 대한 조치 135

III. 집행관의 법적 지위와 책임 138

1. 집행관의 법적 지위 138

2. 집행관의 관할권 139

3. 집행관의 책임 140

IV. 집행관의 보수 149

제3절 독일의 집행관제도 152

I. 독일의 집행관제도의 이해 152

II. 독일 집행관제도 일반 155

1. 집행관 제도의 통일과 근거규정 155

2. 집행관 자격요건, 업무, 지위 157

3. 민영화논의 160

4. 독일 집행관 제도의 개혁 논의 164

III. 집행관제도 개혁 필요성 확인 165

1. 집행관제도 개혁의 필요성 165

2. 집행관의 업무량 167

3. 낮은 비용 대 효과 168

4. 보수 170

IV. 집행관제도의 개혁제안 170

1. 집행관 비용법 및 보수에 관한 논의 170

2. 집행관 관할구역 보호의 완화 189

3. 강제집행에 있어서 사건 해결을 위한 개혁의 영향 201

4. 규제완화의 가능성에 대응한 집행관규칙 202

V. 주 법무차관 실무진 회의에서 다루지 않은 집행관제도 203

1. 집행관으로의 채권압류 업무의 이전 203

2. 강제집행 이외의 다른 직무영역의 개방 210

3. 집행관 교육의 전문대학으로의 전환 215

4. 집행국의 도입 220

VI. 집행관제도 개혁의 의견수렴과 그 평가 227

제4절 프랑스의 집행관제도 230

I. 프랑스 집행관제도의 이해 230

1. 휴이세(Huissier)의 조직 230

2. 집행관(huissier)의 직무내용 231

3. 보조집행관제 231

II. 프랑스 강제집행법의 법원(法源) 232

1. 법령(sources légales) 232

2. 판례(Sources jurisprudentielles) 233

3. 학설(sources dorctrincles) 234

4. 실무관행(Pratiques professionnelles) 234

III. 프랑스 강제집행법의 발전 234

1. 강제집행법의 부분적 개정과 실무의 발전 234

2. 1991-1992년의 프랑스 강제집행법의 근본적인 개정 236

IV. 강제집행의 요건 249

1. 강제집행요건 개관 249

2. 집행권원(le titre exécutoire) 250

3. 집행문(formule exécutoire) 250

V. 프랑스 집행관(huissier de justice)제도의 특색 253

1. 기능 253

2. 연혁과 현행규정 255

3. 권리와 의무 255

4. 직업조직(organisation de la profession) 258

제5절 일본의 집행관제도 260

I. 일본 집행관제도의 이해 260

1. 연혁 260

2. 집행관의 임명 261

3. 집행관 시험제도 261

4. 지위 263

5. 직무관할 264

II. 일본의 집행관제도의 특색 264

1. 집행관의 수입수수료 264

2. 집행에 있어 소송구조자의 특칙 265

3. 집행기록의 보관의무와 당사자의 열람권 265

4. 집행관 직무 대행 266

III. 일본 집행관의 사무분배와 권한 266

1. 법원에 의한 사무분배 제도 266

2. 집행관의 권한 267

3. 집행관의 집행신청 각하권 268

제4장 현행 집행관제도의 문제점과 개선방안 269

제1절 집행관의 의무 269

제2절 집행관의 자격 277

I. 집행관 자격 277

II. 선임방법 및 절차 277

제3절 집행관의 업무집행 방식 281

I. 당사자의 신청 281

II. 사건처리의 지연 281

III. 집행관의 업무처리 방식 282

1. 소극적 업무집행 284

2. 집행관의 부당한 업무집행 287

제4절 적정 집행관의 수 289

제5절 집행관의 보수 293

I. 인건비와 사무소 운영비용 293

II. 집행비용 294

1. 강제경매 294

2. 임의경매 298

제6절 집행관의 임명과 임기 300

제7절 집행관사무소 조직과 관할 304

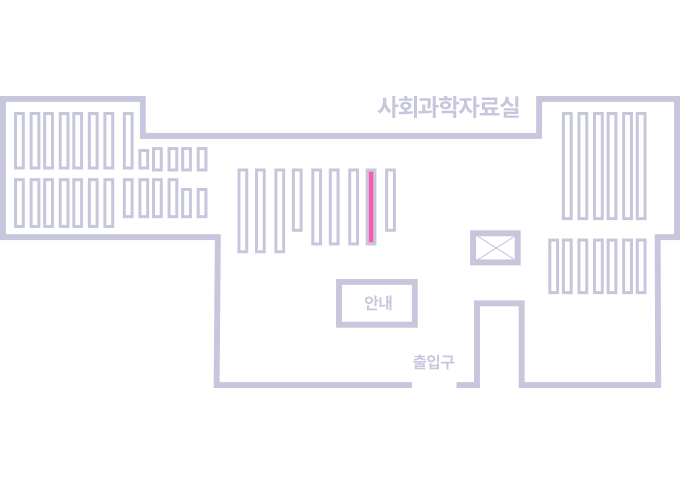

I. 집행관 인원현황 304

II. 관할 304

제8절 집행관의 감독과 책임 306

제9절 보수체계 공개와 국고환수 310

제10절 전자집행 제도의 실시 312

제11절 집행관 및 보조인의 교육 317

I. 집행관 교육 317

1. 집행관 교육의 개요 317

2. 연수대상자 318

3. 연수시기 및 기간 318

4. 연수내용 318

5. 보고사항 319

II. 집행관 보조 인력의 채용 319

III. 집행관 사무원의 교육 321

1. 목적 321

2. 교육시기 및 기간 321

3. 교육계획 321

4. 교육과목 322

5. 교육방법 및 강사위촉 322

제12절 집행관제도의 개선방안 323

I. 사안별 해결 323

1. 임명제도 323

2. 신분상 지위 324

3. 수수료제 325

4. 감독면 325

5. 관행적인 사무집행의 개선 326

6. 합동사무소 326

II. 절차적 측면에서의 문제 해결 327

1. 집행관제도 개혁의 방법론적 구상 329

2. 집행관 직무집행법규의 세칙화 332

III. 조직적 측면에서 문제의 해결 339

1. 집행업무의 민간으로 이양 339

2. 집행관 조직의 법원내부로의 편입 340

IV. 요약 343

제5장 결론 345

참고문헌 354

ABSTRACT 366

그림목차

[그림 1] 독일 법원의 종류와 심급구조 198

[그림 2] 함부르크 구법원 행정조직 221

[그림 3] 뒤스부르크 구법원 행정조직 223

[그림 4] (제목없음) 305

In this dissertation I argued the problem of bailiff system and its improvement directions in Korea. The bailiff has different meaning under the jurisdiction. A bailiff (from Anglo-Norman baillis, baillif, from bail "custody, charge, office"; cf. bail) is a manager, overseer or custodian; a legal officer to whom some degree of authority, care or jurisdiction is committed. Bailiffs are of various kinds and their offices and duties vary greatly. The term was first applied in Norman England to the king's officers charged with local administrative authority, such as sheriffs, mayors, hundreders-the chief officer of a territorial hundred—and the first civil officers of the Channel Islands. The term eventually narrowed to refer to an officer of a hundred court, appointed by a sheriff, and who assisted judges at assizes, served process, executed writs, assembled juries, and collected fines in court. In this later role, the bailiff has essentially replaced the pre-Conquest office of scyldhæta (scultheta). Likewise, in Scotland a bailie was the chief magistrate of a barony (baron bailie) or part of a county, but now refers to a municipal officer corresponding to an English alderman. The district within which the bailiff exercises his jurisdiction is still called his bailiwick. The term bailiff is retained as a title by the chief magistrates of various towns and the keepers of royal castles, such as the High Bailiff of Westminster and the Bailiff of Dover Castle. Under the manorial system a bailiff of the manor represented the peasants to the lord, oversaw the lands and buildings of the manor, collected fines and rents, and managed the profits and expenses of the manor and farm. Bailiffs were outsiders and free men, that is, not from the village. Borough bailiffs would be in charge of the villagers in the town.

The office of bailiff was used in low countries and German-speaking lands such as Flanders, Zealand, the Netherlands, Hainault, and in northern France. Under the Ancien Régime in France, the bailli (earlier baillis), or bailie, was the king's chief officer in a bailiwick or bailiery (bailliage), serving as chief magistrate for boroughs and baronies, administrator, military organizer, and financial agent. In southern France the term generally used was sénéchal who held office in a sénéchaussée. The bailie convened a bailie court (cour baillivale) which was an itinerant court of first instance.

The administrative network of bailiwicks was established in the 13th century over the Crown lands (the domaine royal) by Philip Augustus. They were based on pre-existing tax collection districts (baillie) which had been in use in formerly sovereign territories, e.g., the Duchy of Normandy. Bailie courts, as royal courts, were made superior over existent local courts; these lower courts were called: (i) provost courts (prévôtés royales), sat by a provost (prévôt) appointed and paid by the bailie; (ii) Norman vicomtés, sat by a viscount (vicomte) (position could be held by non-nobles); (iii) elsewhere in northern France, châtellenies, sat by a castellan (châtelain) (position could be held by non-nobles); (iv) or, in the south, vigueries or baylies, sat by a viguier or bayle.

The bailie court was presided over by a lieutenant-bailie (lieutenant général du bailli). Bailie courts had appellate jurisdiction over lower courts (manorial courts, provost courts) but was the court of first instance for suits involving the nobility. Appeal of bailie court judgments lay in turn with the provincial Parliaments. In an effort to reduce the Parlements' caseload, several bailie courts were granted extended powers by Henry II of France and were thereafter called presidial courts (baillages présidiaux). Bailie and presidial courts were also the courts of first instance for certain crimes (previously the jurisdiction of manorial courts): sacrilege, treason, kidnapping, rape, heresy, money defacement, sedition, insurrection, and illegal bearing of weapons.

By the late 16th century, the bailie's role had become mostly symbolic, and the lieutenant-bailie was the only one to hear cases. The administrative and financial role of the bailie courts declined in the early modern period (superseded by the king's royal tax collectors and provincial governors, and later by intendants), and by the end of the 18th century, the bailiwicks, which numbered in the hundreds, had become purely judicial.

In medieval France court bailiffs did not exist as such, but their functions were carried out by several court officers. The ussier (modern huissier), or usher, originally the doorkeeper, kept order in the court. The somoneor (mod. semonneur), or court crier, adjourned and called the court to order and announced its orders or directions. The bedel (mod. bedeau), or beadle, was the court's messenger and served process, especially summonses (sumunse, somonse, mod. semonce). And finally the sergens (mod. sergent), or tipstaff, enforced judgments of the court, seized property, and made arrests. The tipstaff's badge of authority was his verge, or staff, made of ebony, about 30 cm long, decorated with copper or ivory, and mandatory after 1560.

The Parlement courts consolidated most of these functions in its tipstaff (varlet), and the rest of the court system followed suit as the tipstaff was given the broadest powers. During the Renaissance, the four officers were reduced to two - the huissier and sergent - who took on all these functions, with the distinction being that the huissier served in higher courts and sergent in bailie courts (sergent royal) and manorial courts (sergent de justice). In 1705 the two professions were fused by royal edict under the name huissier.

Civilian enforcement officers are employed by Her Majesty's Courts and Tribunals Service and carry out enforcement for magistrates' courts - this mainly involves collection of unpaid fines given by the court and the execution of arrest warrants.

County court bailiffs are employed by Her Majesty's Courts and Tribunals Service and carry out enforcement for county courts - mainly involving payment of unpaid county court judgments. They can seize and sell goods to recover a debt. They can also affect and supervise the possession of the property and the return of goods under hire purchase agreements, and serve court documents. They also execute arrest warrants and execute search warrants. Service of personal papers such as oral examinations and divorce papers can also aid the Tipstaff in their duties if necessary.

High Court Enforcement Officers are authorized by the Lord Chancellor to execute High Court writs. They can seize and sell goods to cover the amount of a debt owed. They can also enforce and supervise the possession of property and the return of goods. They replaced Sheriff's Officers in April 2004. Legislation relating the High Court Enforcement Officers includes the Sheriffs Act 1887, The High Court Enforcement Officers Regulations 2004 and the Courts Act 2003.

Unlike a County Court Bailiff, who is a civil servant, an HCEO is an Agent of the High Court appointed by the Lord Chancellor. In order to appoint and HCEO, a writ has to be obtained from the County Court, and be presented to the High Court. The debt must be over £600 and it cannot be one where judgement has been obtained for a debt owed under the Consumer Credit Act 1974.

Certificated bailiffs are employed by private companies and enforce a variety of debts on behalf of organizations such as local authorities. They can seize and sell goods to cover the amount of the debt owed. They also hold a certificate, which enables them, and them alone, to levy distress for rent, road traffic debts, council tax and non-domestic rates. Certificated bailiffs are required to gain peaceable entry into property before a levy of goods inside a property can take place. They cannot enforce the collection of money due under High Court or county court orders. Certificated Bailiffs are increasingly being used by Local Authroties and HMCTS to carry out the enforcement of both Bail and Non-Bail arrest warrants, this usually involves the Bailiff locating a wanted person and taking them into custody usually a Police Officer will be present to assit the Bailiff with the arrest and transportation of the prisioner to Court however this is not a legal requirement.

Non-certificated bailiff are employed by private companies and are entitled to recover the money owed for a variety of debts by seizing and selling goods but cannot levy distress for rent, road traffic debts, council tax or non-domestic rates, or enforce the collection of money due under High Court or county court orders.

All the above bailiffs will be replaced by enforcement agents when the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007, comes into force. Water bailiffs also exist in England and Wales to police bodies of water and prevent illegal fishing. They are generally employees of the Environment Agency and are to be deemed as a Constable with the same powers and privilages for the purpose of the enforcement of the Salmon and Freshwater Fisheries Act 1975. Jury bailiffs are court ushers who monitor juries during their deliberations and during overnight stays.

In England & Wales, the bailiff of a franchise or liberty is the officer who executes writs and processes, and impanels juries within the franchise. He is appointed by the lord of such franchise (who, in the Sheriffs Act 1887, §34, is referred to as the bailiff of the franchise).

The bailiff of a sheriff is an under-officer employed by a sheriff within a county for the purpose of executing writs, processes, distraint and arrests. As a sheriff is liable for the acts of his officers acting under his warrant, his bailiffs are annually bound to him in an obligation with sureties for the faithful discharge of their office, and thence are called bound bailiffs. They are also often called 'bum-bailiffs', or, shortly, 'bums'. The origin of this word is uncertain; the New English Dictionary suggests that it is in allusion to the mode of catching the offender. Special bailiffs are officers appointed by the sheriff at the request of a plaintiff for the purpose of executing a particular process. The appointment of a special bailiff relieves the sheriff from all responsibility until the party is arrested and delivered into the sheriff's actual custody.

By the County Courts Act 1888, it is provided that there shall be one or more High Bailiffs, appointed by the judge and removable by the Lord Chancellor; and every person discharging the duties of high bailiff is empowered to appoint a sufficient number of able and fit persons as bailiffs to assist him, whom he can dismiss at his pleasure. The duty of the high bailiff is to serve all summonses and orders, and execute all the warrants, precepts and writs issued out of the court. The high bailiff is responsible for all the acts and defaults of himself, and of the bailiffs appointed to assist him, in the same way as a sheriff of a county is responsible for the acts and defaults of himself and his officers. By the same act (§49) bailiffs are answerable for any connivance, omission or neglect to levy any such execution. No action can be brought against a bailiff acting under order of the court without six days' notice (§52). Any warrant to a bailiff to give possession of a tenement justifies him in entering upon the premises named in the warrant, and giving possession, provided the entry be made between the hours of 6 a.m. and 10 p.m. (§142). The Law of Distress Amendment Act 1888 enacts that no person may act as a bailiff to levy any distress for rent, unless he is authorized by a County Court judge to act as a bailiff.

Many in the United States use the word bailiff colloquially to refer to a peace officer providing court security. More often, these court officers are sheriff's deputies, marshals, corrections officers or constables. The terminology varies among (and sometimes within) the several states. From its staff, the Court may appoint by court order bailiffs as peace officers, who shall have, during the stated terms of such appointment, such powers normally incident to police officers, including, but not limited to, the power to make arrests in a criminal case, provided that the exercise of such powers shall be limited to any building or real property maintained or used as a courthouse or in support of judicial functions. In rural areas, this responsibility is often carried out by the junior lawyer in training under the judge's supervision called a law clerk who also has the title of bailiff.

Whatever the name used, the agency providing court security is often charged with serving legal process and seizing and selling property (e.g., replevin or foreclosure). In some cases, the duties are separated between agencies in a given jurisdiction. For instance, a court officer may provide courtroom security in a jurisdiction where a sheriff handles service of process and seizures.

In the New York State Unified Court System, Court Officers, are responsible for providing security and enforcing the law in and around court houses. Under New York State penal code, they are classified as "peace officers." New York State Court Officers are able to carry firearms both on and off duty, and have the power to make warrantless arrests both on and off duty anywhere in the State of New York. They also have the authority to make traffic stops.

This dissertation spotted various issues regarding Korean bailiff system focusing on the disadvantages or problem and I compared those issues with other jurisdiction (i.e., United Kingdom, U.S., Germany, France, Japan). Especially, I proposed improvement plan including eligibility of bailiff, term of office, training and education, open the income, supervising method, electronic auction. Most of all, I believe the best policy concerning the innovation of bailiff system is bring the system to the judicial organization. Only this scheme can reformed and remove the ills. Hopefully, this research may ignite the issue on the revolutionary policy of the bailiff in Korea.| 번호 | 참고문헌 | 국회도서관 소장유무 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 국세징수법, 한일조세연구소, (2004). | 미소장 |

| 2 | 물권법, 법문사, (1999). | 미소장 |

| 3 | 통합도산법, 박영사 (2006). | 미소장 |

| 4 | 통합도산법 분석, 법률OS (2005). | 미소장 |

| 5 | 한국도산법의 선진화방안, 법률OS (2003). | 미소장 |

| 6 | 신민사집행법, 박영사, (2009). | 미소장 |

| 7 | 부동산유치권, 도서출판 LTS, (2009). | 미소장 |

| 8 | A Study on the Controversial Points and Improvement Plan for the Procedure of Deposition on Default | 소장 |

| 9 | 국세청, 국세통계연보, 각 연도. | 미소장 |

| 10 | 국회법제사법위원장, 채무자회생 및 파산에 관한 법률대안 (2005. 2. 28). | 미소장 |

| 11 | 강제집행 등과 체납처분의 절차조정법의 입법론적 연구, 서울시립대학교 박사학위 논문, (2006). | 미소장 |

| 12 | 부동산경매에서 유치권의 개선에 관한 연구, 건국대학교대학원 박사학위논문, (2008). | 미소장 |

| 13 | 유치권의 공시기능 강화방안에 관한 연구  |

미소장 |

| 14 | 미국의 사법제도상 집행관의 지위, 재판자료 84집 (1999. 11), 외국사법연수논집(17) 법원행정처, (1999), 271-329면. | 미소장 |

| 15 | 김성룡, 채무자회생 및 파산에 관한 법률안의 개략적 검토, 법률신문 (2003.6. 12). | 미소장 |

| 16 | 유치권과 저당권의 효력관계 | 소장 |

| 17 | 채무자회생․파산이론&실무, 법문출판사 (2006). | 미소장 |

| 18 | 독일의 사법제도 소고 : 법관 아닌 사법기관을 중심으로, 법조제38권 6호 (통권393호) (1989. 6), 103-119면. | 미소장 |

| 19 | 統合 倒産法案의 主要爭點 | 소장 |

| 20 | 도산제도의 법경제학 : 도산3법 통합의 바람직한 방향 KOREI(2003. 3). | 미소장 |

| 21 | (A) Study on the Status of Lien Holder in Real Estate Auction  |

미소장 |

| 22 | 김현석, 미국기업파산법, 고시계 (2005). | 미소장 |

| 23 | 미국 연방파산법상 자동정지제도와 채권자 보호제도 | 소장 |

| 24 | 전자입찰과 청렴도 관계에 관한 실증분석-중앙정부와 지방자치단체를 중심으로, 한국조달연구원, (2006). | 미소장 |

| 25 | 부동산 경매범죄로서의 허위 유치권에 관한 연구 | 소장 |

| 26 | 법무부, 프랑스의 사법제도, (1997), 715-721면. | 미소장 |

| 27 | 법원행정처, 사법연감 (2000-2010). | 미소장 |

| 28 | 법원행정처, 집행관 감독지침, 법원행정처 사법행정 간행물 (2009). | 미소장 |

| 29 | 서울중앙지방법원, 회생사건실무(상) (2006). | 미소장 |

| 30 | 설범식, 도산절차가 소송절차 등에 미치는 영향, 대전지방법원 실무연구자료제3권, (1999). | 미소장 |

| 31 | 도산법제의 개선방안에 관한 연구 | 소장 |

| 32 | 부동산경매제도의 개선방안에 관한 법적 연구 | 소장 |

| 33 | Translation : Geltung und Wirksamkeit des Rechls  |

미소장 |

| 34 | 프랑스강제집행법 서설 | 소장 |

| 35 | 프랑스 강제집행법중의 우선주의, 민사법의 실천적과제: 閑道정환담교수 화갑기념, 법문사 (2000), 225-238면. | 미소장 |

| 36 | 영국의 도산법, 한국법제연구원 (1998). | 미소장 |

| 37 | 이민걸, 회사정리절차와 강제집행과의 관계, 재판자료 제2집 (1996). | 미소장 |

| 38 | 美國法上 擔保權實行 및 强制執行節次와 債權者의 請求金額 擴張에 관한 問題 | 소장 |

| 39 | 집달관에 대한 제도적 고찰과 개혁에 관한 소고, 사법연구자료 11집(1984. 4), 193-232면. | 미소장 |

| 40 | 부동산 경매에 있어서 유치권의 문제점과 개선방안 : 집행관의 현황조사보고의 문제점을 중심으로 | 소장 |

| 41 | 프랑스 민사소송에 있어서의 레페레(Refere), 재판자료 93집 (2001.12), 외국사법연수논집 (21), (2001), 303-370면. | 미소장 |

| 42 | 회사정리법(상)(하), 한국사법행정학회 (2002). | 미소장 |

| 43 | 지방세 체납액 효율적 징수를 위한 한국자산관리공사의 공매대행제도에 대한 소고,上 | 소장 |

| 44 | 가처분절차에서 소명, 한국민사소송법학회지, 제13권, 제2호,pp.240-276, (2009). | 미소장 |

| 45 | Study On Problems And Measures of Lien in the Practical Procedure About Real Estate Auction | 소장 |

| 46 | “독일 최고법원의 재판실무현황” 사법개혁과 세계의 사법제도 VI, 한국사법행정학회(2008), 402면. | 미소장 |

| 47 | 파산절차가 계속중인 민사소송에 미치는 영향-판결절차와 집행절차를 포함하여-, 파산법의 제문제(하), 제3집. | 미소장 |

| 48 | 도산절차와 소송․절차․강제집행․보전처분, 재판실무연구 (2000). | 미소장 |

| 49 | 한국산업은행, 도산법 개정방안 (2001). | 미소장 |

| 50 | 영국에서의 금전채권에 관한 판결의 강제집행 : High Court에서의 집행방법을 중심으로, 재판자료 제47집 외국사법연수논집(7), (1989.12), 35-94면. | 미소장 |

| 51 | 행정자치부, 지방세정연감, (2005). | 미소장 |

| 52 | 헌법재판소 2002. 6. 27. 2000헌마642, 2001헌바12(병합) 전원재판부 [부동산중개업법 제15조 등 위헌확인] [헌공 제70호] | 미소장 |

| 53 | 헌법재판소 판례집 제2권 (1990). | 미소장 |

| 54 | 獨逸 强制執行法에 관한 硏究 | 소장 |

| 55 | 부동산 경매절차상 허위·과장유치권 근절을 위한 대책 | 소장 |

| 56 | 强制執行法總論, 法律學全集36-1, 156頁. | 미소장 |

| 57 | 執行官事務の實情と改革の方向性, 金融法務事情1628號(2001. 12),16-18⾴. | 미소장 |

| 58 | 日本法曹會, 執行官提要(1998). | 미소장 |

| 59 | ドイツにおける執行官制度の民營化に關する議論1, 比較法學 第41卷2號(通卷第84號), 早稻田大學比較法硏究所(2007)107-146⾴. | 미소장 |

| 60 | ドイツにおける執行官制度の民營化に關する議論2, 比較法學 第41卷3號(通卷第85號), 早稻田大學比較法硏究所(2008) 1-44⾴. | 미소장 |

| 61 | ドイツにおける執行官制度の民營化に關する議論3ㆍ完, 比較法學 第42卷2號(通卷第87號), 早稻田大學比較法硏究所(2009) 1-46⾴. | 미소장 |

| 62 | ドイツ「執行官制度の改革のための法律案」試譯1, 比較法學42卷 3號(通卷第88號), 早稻田大學比較法硏究所(2009) 193-226⾴. | 미소장 |

| 63 | ドイツ「執行官制度の改革のための法律案」試譯2ㆍ完, 比較法學 43卷1號(通卷第89號), 早稻田大學比較法硏究所(2009) 119-140⾴. | 미소장 |

| 64 | 執行官事務の實情と改革の方向性, 金融法務事情1628號(2001. 12), 金融財政事情硏究所(2001) 16-18⾴. | 미소장 |

| 65 | 條解會社更生法(上)․下), 弘文堂(1999). | 미소장 |

| 66 | 會社更生計劃におけゐ公正, 衡平と遂行可能3についての一考察, 裁判と法(下). | 미소장 |

| 67 | 條解民事再生法, 弘文堂(2003). | 미소장 |

| 68 | 會社更生の性格と構造(四), 法學協會雜誌第86券第4號. | 미소장 |

| 69 | Auctions: Social Construction of Value, Univ. of California Press (1990), http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1727409. | 미소장 |

| 70 | Simultaneous Ascending Auctions, in Cramton, Peter; Shoham, Yoav; Steinberg, Richard, Combinatorial Auctions, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, (2006). | 미소장 |

| 71 | Provisional and Protective Remedies: The British Experience of the Brussels Convention  |

미소장 |

| 72 | On the enforcement of specific performance in Civil Law countries  |

미소장 |

| 73 | Bailiff Powers and Civil Judgment Enforcement, (Jan. 2011). | 미소장 |

| 74 | The Innovative German Approach to Consumer Debt Relief: Revolutionary Changes in German Law, and Surprising Lessons for the United States  |

미소장 |

| 75 | Temporary and Permanent Buyout Prices in Online Auctions, Management Science (Informs) 53(5): pp.814–833, doi:10.1287/mnsc.1060.0650, http://mansci.journal.informs.org/cgi/content/abstract/53/5/814 (May 2007). | 미소장 |

| 76 | with the Assistance of Aoi Inoue Hughes Hubbard & Reed, LLP, Selected Materials in International Litigation and Arbitration, Practising Law Institute International Arbitration 2011 PLI Order No. 30336 New York City, (Mar. 7, 2011). | 미소장 |

| 77 | Journal of Economic Literature Classification System, American Economic Association, http://aea-web.org/journal/jel_class_system.html (retrieved 2012. 7. 25) (D: Microeconomics, D4: Market Structure and Pricing, D44: Auctions). | 미소장 |

| 78 | The Ebay Price Guide: What Sells for What. No Starch Press, (2006). | 미소장 |

| 79 | Bankruptcy resolution: Direct costs and violation of priority of claims  |

미소장 |

| 80 | A New Approach to Corporate Reorganizations, 101 Harvard Law Review 775 (1988) (김화진譯), 회사정리와 지분의 분배: 제안, 국제거래법연구 제2집(1993. 6), 283면. | 미소장 |

| 81 | The Theory of Money and Financial Institutions: Volume 1, Cambridge, Mass., USA: MIT Press, pp.213-219, (Mar. 2004). | 미소장 |

| 82 | Auctions and Bidding  |

미소장 |

| 83 | English Civil Procedure–Fundamentals of the New Civil Justice System (2003). | 미소장 |

| 84 | Tatworth Candle Auction  |

미소장 |

| 85 | Putting Auction Theory to Work, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, (2004). | 미소장 |

| 86 | Theory and Practice  |

미소장 |

| 87 | (ed.), Methods of Execution of Orders and Judgments in Europe (1996). | 미소장 |

| 88 | History of Auctions: From ancient Rome to today's high-tech auctions, Auctioneer, archived from the original on May 17, 2012, http://web.archive.org/web/20080517071614/http://auctioneersfoundation.org/news_detail.php?id=5094 (retrieved 2012. 11. 22)[dead link]. | 미소장 |

| 89 | The Real Estate Investor's Handbook: The Complete Guide for the Individual Investor, Ocala, Florida: Atlantic Publishing Company, pp. 89–90, (2006). | 미소장 |

| 90 | The eBay Effect: Online auctions give new life to this alternative commercial real estate selling strategy  |

미소장 |

| 91 | The Economist, The Heyday of the Auction, The Economist 352 (8129): pp.67-68, (1999. 7. 24). | 미소장 |

| 92 | Online reverse auctions: Common myths versus evolving reality, Business Horizons (Kelley School of Business, Indiana University) 50 (5): pp.373-384, doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2007.03.003 (Sep.–Oct. 2007). | 미소장 |

| 93 | Auction Theory, San Diego, USA: Academic Press, (2002). | 미소장 |

| 94 | The Enforcement of Judgments in Europe (2000). | 미소장 |

| 95 | General Report Enforcement, in: Marcel Storme (ed), Procedural Laws in Europe towards Harmonisation (2003), p.81 et seq. | 미소장 |

| 96 | How to Collect Your Judgment, Directing Attorney, Legal Aid, Orange County, at 8. available at http://www.docstoc.com/search/free-legal-name-change-document (last visited on May 1, 2012). | 미소장 |

| 97 | Gerichtsvollzieher handelt beim Abschluβ von Verwahrungsvertragen fur den Justizfiskus, Juristen Zeitung Jahrg. 55, Hft. 7 (2000. 4) 359 J.C.B. Mohr (2000). | 미소장 |

| 98 | Ubertragung des Verfahrens der Abnahme der Eidesstattlichen Versicherung auf den Gerichtsvollzieher, (Der) Deutsche Rechtspfleger Jahr. 106, Hft 10 (1998. 10) 409 Gieseking (1998). | 미소장 |

| 99 | Die Neuorganisation des Gerichtsvollzieherwesens in Deutschland: Wissenschaftliches Gutachten Erstellt im Auftrag des Deutschen Gerichtsvollzieherbundes E.V (German), Nomos Verlagsges.mbh, Co (2006. 10). | 미소장 |

| 100 | Konturen eines Europäischen Systems des Einstweiligen Rechtsschutzes, Europäisches Wirtschafts- und Steuerrecht (2000), p.11 et seq. | 미소장 |

| 101 | Einheitlicher Auftrag an Gerichtsvollzieher, (Der) Deutsche Rechtspfleger Jahr. 110, Hft 2 (2002. 2) 88-89, Gieseking (2002). | 미소장 |

| 102 | Verbraucherinsolvenz und Restschuldbefreiung: Eine Einfuhrung fur Schuldner, Schuldnerberater, Richter, Rechtspfleger, Gerichtsvollzieher, Anwalte und Steuerberater mit Antworten auf alle wichtige, C.H. Beck (2002). | 미소장 |

| 103 | (Das) Kostenwesen der Gerichtsvollzieher: Kommentar, R. v. Decker's (2006). | 미소장 |

| 104 | Das Kostenwesen der Gerichtsvollzieher, Decker, Heidelberg (Jan. 1, 2002). | 미소장 |

| 105 | Die drei Eidesstattlichen Versicherungen vor dem Gerichtsvollzieher, Monats-schrift fur Deutsches Recht: Zeitschrift fur die Zivilrechts-Praxis Jahrg. 54, Hft. 4 (2000. 2) 195, Otto Schmidt (2000). | 미소장 |

| 106 | Der Staatsanwalt als Gerichtsvollzieher? Neue Zeitschrift fur Strafrecht Jahrg. 20, Hft. 4 (2000. 4) 180 C.H. Beck (2000). | 미소장 |

| 107 | Auslandszustellung durch den Gerichtsvollzieher, Neue juristische Wochenschrift Jahrg. 56, Hft. 22 (2003. 5) 1571-1572 C.H. Beck (2003). | 미소장 |

| 108 | Die Klausur im Zwangsvollstreckungsrecht; Die Klausur im ZVR., 4. Aufl. (2011), S. 209. (Vahlen Jura-Referendariat). | 미소장 |

| 109 | Einstweiliger Rechtsschutz: Generalbericht, in: Marcel Storme (ed.) Procedural Laws in Europe towards harmonisation (2003), p.143 et seq. | 미소장 |

| 110 | Die Privatisierung Des Gerichtsvollzieherwesens (2008. 5). | 미소장 |

| 111 | Die Zwangsvollstreckung durch den Gerichtsvollzieher, Neue juristische Wochenschrift Jahrg. 47, Hft. 6 (1994. 2) 352 C.H. Beck (1994). | 미소장 |

| 112 | Vollstreckung durch den Gerichtsvollzieher: Sachpfandung, eidesstattliche Versicherung, GVGA und GVO, Verl. fur die Rechtsund Anwaltspraxis (2000). | 미소장 |

| 113 | Gerichtsvollzieher in Vergangenheit und Zukunft. In: Zeitschrift für Zivilprozess (ZZP), 119. Bd., (2006), S. 87-108. | 미소장 |

| 114 | Les Huissiers de Justice (2011). p.710. | 미소장 |

| 115 | The History of the 'Huissier de Justice' in the low Countries, Maastricht European Private Law Institute Working Paper No. (2011/15). | 미소장 |

| 116 | The History of the 'Huissier de Justice' in the low Countries, Enforcement and Enforceability: Tradition and Reform, C.H. van Rhee, A. Uzelac, eds., Antwerp: Intersentia, 2010 M-EPLI Working Paper No. (2011/15). | 미소장 |

| 117 | Profession Huissier de Justice, Paris, EJT, (1999), p.219. | 미소장 |

| 118 | THE AUTHORITY OF A MICHIGAN SHERIFF TO DENY LAW ENFORCEMENT POWERS TO A DEPUTY  |

미소장 |

| 119 | Nouveau Formulaire des Actes Usuels des Huissiers de Justice: Procedure Civile, Procedure Penale Devant les Differentes Juridictions Repressives, Voies d'execution, Actes Divers, Litec (1988). | 미소장 |

| 120 | Vers un Concept Européen du Droit de l'exécution, in: Isnard/Normand, Le Droit Processuel et le Droit de l'exécution (2002), p.165 et seq. | 미소장 |

| 121 | Compétence et exécution des Jugements en Europe (3rd ed. 2003). | 미소장 |

| 122 | (ed.), L'aménagement du Droit de l'exécution dans l’espace Communautaire–bientôt les Premiers Instruments (2003). | 미소장 |

| 123 | (ed.), Nouveaux Droits dans un Nouvel Espace Européen de Justice: Le Droit Processuel et le Droit de l'exécution (2002). | 미소장 |

| 124 | Voies d'éxécution et Procédures de Distribution, (08/01/2009) (8e édition). | 미소장 |

| 125 | Voies d'exécution et Procédures de Distribution, 18 éd., Paris, Dalloz, (1995), n°6. | 미소장 |

| 126 | Droit de l'exécution des Peines, (2012-2013) (16/12/2011) (4e édition). | 미소장 |

| 127 | Le Droit Européen à l'exécution des Jugments, Revue des Huissiers de Justice (2002), p.6 et seq. | 미소장 |

| 128 | Revue des Huissiers de Justice (2003), p.4 et seq. | 미소장 |

| 129 | Le Droit de l'exécution selon la Jurisprudence de la Cour Européenne des Droits de l'homme: Analyse et Prospective, in: Normand/Isnard, le Droit Processuel et le Droit de l'exécution (2002), p.195 et seq. | 미소장 |

| 130 | Tous les Textes Relatifs aux Procédures Civiles d'exécution (acteurs, règles) se Trouvent dans le Code de l'exécution, EJT, (2008). | 미소장 |

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

| 전화번호 |

|---|

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 번호 | 발행일자 | 권호명 | 제본정보 | 자료실 | 원문 | 신청 페이지 |

|---|

도서위치안내: / 서가번호:

우편복사 목록담기를 완료하였습니다.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

저장 되었습니다.