권호기사보기

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 대표형(전거형, Authority) | 생물정보 | 이형(異形, Variant) | 소속 | 직위 | 직업 | 활동분야 | 주기 | 서지 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 연구/단체명을 입력해주세요. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

* 주제를 선택하시면 검색 상세로 이동합니다.

영문목차

List of Figures=ⅶ

List of Tables=xi

Preface=xiii

Abbreviations=xv

1. Introduction=1

2. The Management of Wetland Resources=9

3. Indigenous Knowledge and Wetland Management=31

4. Wetland Resources in Illubabor=51

5. The Research Approach=75

6. The Study Wetlands=95

7. The Hydrology of Valley Bottom Wetlands=121

8. Indigenous Wetland Management in Illubabor=149

9. Indigenous and Scientific Wetland Knowledge=181

10. Sustainable Hydrological Management of Wetlands=205

Bibliography=225

Index=241

Figure 4.1. The Location of Ethiopia and the Ethiopian highlands=52

Figure 4.2. The seasonal pattern of rainfall in Ethiopia=53

Figure 4.3. The location of Illubabor zone within Ethiopia=55

Figure 4.4. Administrative divisions (weredas) within Illubabor zone=55

Figure 4.5. The seasonal pattern of rainfall and temperature recorded at Metu, central Illubabor(1967-1997)=58

Figure 4.6. The dominant vegetation in Illubabor zone=58

Figure 4.7. Estimates of the total area of wetland under cultivation (ha) in Illubabor zone since 1990=69

Figure 4.8. Hurumu wetland under cultivation in 1994=70

Figure 4.9. Hurumu wetland in a degaded state during 1997=70

Figure 4.10a. Traditional wetland management=72

Figure 4.10b. The intensification of wetland utilization=72

Figure 5.1. The location of the study area within Illubabor=76

Figure 5.2. Summary of the classification and study site selection process=78

Figure 5.3. The dipwell apparatus=81

Figure 5.4. Farmers construct a resource map of Bake Chora wetland using a variety of natural materials=91

Figure 5.5. Field sketch of a seasonal calendar (including rainfall) produced by farmers at Dizi wetland=91

Figure 6.1. The final classification of wetlands into three size categories=96

Figure 6.2. The inflow-outflow characteristics of wetlands in the study area=96

Figure 6.3. Wetland order in the study area=97

Figure 6.4. Wetland shape in the study area=97

Figure 6.5. A conceptual model of wetland development based on the observation of wetland characteristics in the study area=99

Figure 6.6. Location of the study wetlands within the study area=101

Figure 6.7. A wetland agricultural calendar showing the timing of the main land use options=105

Figure 6.8. Chebere wetland=107

Figure 6.9. Wangeneye wetland (under maize cultivation)=107

Figure 6.10. Bake Chora wetland=110

Figure 6.11. Hurumu wetland=110

Figure 6.12. Tulube wetland(1996)=113

Figure 6.13. Tulube wetland(1999)=113

Figure 6.14. Dizi wetland=116

Figure 6.15. Anger wetland=116

Figure 6.16. Supe wetland=118

Figure 7.1. The average monthly rainfall in the study area (central Illubabor)=122

Figure 7.2. The average monthly rainfall (Dizi, Sor and Gore) during the study period(August 1997-July 1998)=122

Figure 7.3. Monthly rainfall during the study period recorded at each gauge=123

Figure 7.4. Rainfall during the study period compared to the 31 year average of Metu, Dizi, Gore and Sor=123

Figure 7.5. The general trend in water table levels during the study period=125

Figure 7.6. Mean weekly water table elevation in the currently undrained study wetlands (August 1997-July 1998)=127

Figure 7.7. Mean weekly water table elevation in the currently drained and degraded study wetlands (August 1997-July 1998)=127

Figure 7.8. The range of mean weekly water table elevations recorded at each study wetland (August 1997-July 1998)=128

Figure 7.9. The spatial distribution of wetland hydrological characteristics in the study wetlands=131

Figure 7.10. The relationship between dipwell groups=133

Figure 7.11. Mean weekly pH levels in the study wetlands=138

Figure 7.12. Range of pH values in each study wetland (August 1997-July 1999)=138

Figure 7.13. Mean weekly pH levels recorded at the top and bottom of each wetland (August 1997-July 1999)=139

Figure 7.14. The mean weekly electrical conductivity in the study wetlands (August 1997-July 1999)=140

Figure 7.15. The mean weekly electrical conductivity at the top and bottom of the study wetlands (August 1997-July 1999)=140

Figure 7.16. Mean monthly nitrate and phosphate levels recorded in the study wetlands (August 1997-July 1999)=142

Figure 8.1. Farmer perceptions of rainfall at each wetland=151

Figure 8.2. Farmer perceptions of water table elevation at each site (cultivated)=153

Figure 8.3. Farmer perceptions of water table elevation at each site (uncultivated)=154

Figure 8.4. The seasonal calendar of wetland farming activities produced by Supe farmers=161

Figure 8.5. The practice of ditch blocking as a means of regulating water supply to the wetland (pictured here at Wangeneye)=163

Figure 8.6. The head of Bake Chora wetland showing a range of land uses including the reservation of cheffe=166

Figure 8.7. Cheffe reservation alongside maize cultivation in Anger wetland=167

Figure 8.8. Dizi farmers' wetland management knowledge and its origins=174

Figure 8.9. Indigenous pest management technology? A scarecrow in Bake Chora wetland=177

Figure 9.1. Farmers' perceptions of rainfall compared to rainfall records=183

Figure 9.2. Farmers' perceptions of water table elevation compared to hydrological records=186

Figure 9.3. Farmers' perceptions of water table compared to the hydrological data=189

Figure 9.4. The water table typology in Bake Chora wetland and the location of an area of discoloured maize=193

Figure 9.5. The relationship between farmers' wetland knowledge and that generated by hydrological monitoring=196

Figure 9.6. The mean weekly water table in Bake Chora wetland and the timing of farmers' main hydrological management activities=197

Figure 9.7. The mean weekly water table at Dizi wetland and the timing of farmers' main hydrological management activities=198

Figure 9.8. The mean weekly water table at Wangeneye wetland and the timing of farmers' main hydrological management activities=200

Figure 9.9. Weekly water table levels in lower Wangeneye wetland=200

Figure 10.1. The variable land use within Supe=207

Figure 10.2. A conceptual model of the current situation of cultivation and abandonment in the wetlands=208

Figure 10.3. The degraded wetland of Goma Gabriel wetland near Bure, pictured after several years of complete cultivation in 1996=209

Figure 10.4. Possible strategies for managing wetland regeneration=211

Figure 10.5. A framework for empowering IK resources=217

Table 1.1. The distribution of wetland functions, products and attributes among wetland types=2

Table 2.1. A hydrogeomorphic classification system for wetlands=11

Table 2.2. A wetland typology derived from ecological and geomorphological wetland classifications=13

Table 3.1. The contrasting ideologies of scientific and indigenous knowledge=36

Table 3.2. A framework for incorporating IK in development=43

Table 4.1. Agroclimatic zones of Ethiopia=57

Table 4.2. The percentage of each wereda area occupied by wetlands=63

Table 4.3. Guidelines for wetland development as established by the Natural Disaster Prevention Committee(1998)=67

Table 5.1. Checklist of information collected during PRA sessions=92

Table 6.1. The wetland typology results=98

Table 6.2. Study wetlands and their development stages=100

Table 6.3. The location and general characteristics of each study wetland=102

Table 6.4. The hydrological characteristics of each study wetland=103

Table 6.5. The land use characteristics of each study wetland=104

Table 7.1. Summary of the hydrological characteristics of each cluster of dipwells=129

Table 7.2. Number of weeks with surface water at each dipwell=129

Table 7.3. Classification of Ksat values in each dipwell according to FAO(1963)=135

Table 7.4. Correlation matrices for mean phosphate and nitrate concentrations=142

Table 7.5. Summary details of chemical concentrations recorded at each wetland=143

Table 7.6. Summary of the impact of agricultural utilization on the wetland hydrological regime=146

Table 8.1. Differences in perceptions of high and low rainfall levels between sites=152

Table 8.2. Differences in farmers' perceptions of high and low water table levels=155

Table 8.3. Tulube farmers' perceptions of water colour=157

Table 8.4. Summary of wetland seasonal farming calendars=162

Table 8.5. Tools utilized in the wetland farming system=164

| 등록번호 | 청구기호 | 권별정보 | 자료실 | 이용여부 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

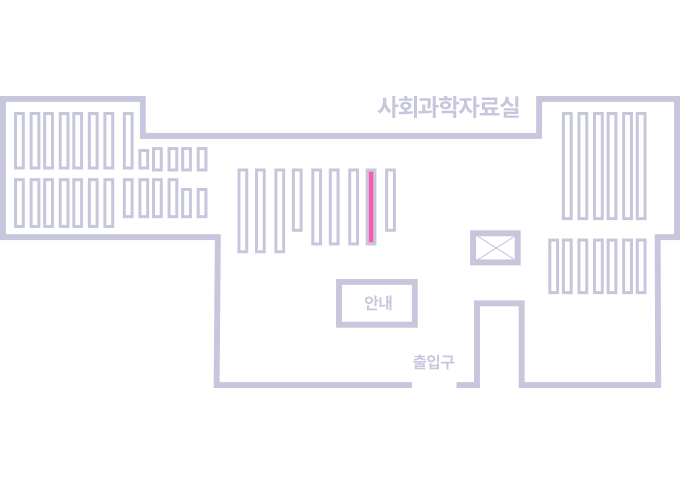

| 0000987861 | 333.9180963 D621i | 서울관 서고(열람신청 후 1층 대출대) | 이용가능 |

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

| 전화번호 |

|---|

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 번호 | 발행일자 | 권호명 | 제본정보 | 자료실 | 원문 | 신청 페이지 |

|---|

도서위치안내: / 서가번호:

우편복사 목록담기를 완료하였습니다.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

저장 되었습니다.