권호기사보기

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 대표형(전거형, Authority) | 생물정보 | 이형(異形, Variant) | 소속 | 직위 | 직업 | 활동분야 | 주기 | 서지 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 연구/단체명을 입력해주세요. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

* 주제를 선택하시면 검색 상세로 이동합니다.

Title page

Contents

Glossary 12

Introduction 19

CHAPTER 1. Manufacturing compliance with 'rule by design' 27

1.1. Transitional scenarios in China and the state's 'rule by design' 29

1.2. Manufacturing compliance in the state-individual interaction 32

Coercion or consent: why coercion alone cannot do the work 33

Generating compliance: a two-actors model and the state's options 35

Constraints, choices, and state-individual interaction in transitional situations 38

Conclusions 40

References 41

CHAPTER 2. Who gets what and how: governance based on subpopulations 45

2.1. How do entitlements differ: differentiation in benefit entitlement 46

2.2. Pension reforms in China: a de-synchronised story 48

2.3. Generosity and coverage: segmented resource allocation 56

The pension plans for government employees (PGE) and public institution employees (PPIE) 56

The pension plan for enterprise employees (PEE) 58

The pension plan for urban non-salaried residents (PUR) and rural residents (PRR) 61

Conclusions 62

References 64

CHAPTER 3. Who deserves benefits and why - constructingfairness, pension expectations,and subjectivity 67

3.1. Text analysis of state discourses 68

3.2. Pension reforms as instruments of broader socio-economic reforms 76

3.3. Reconstructing fairness and deservingness in welfare redistribution 84

Redistribution among different social groups 84

Redistribution between different generations 92

3.4. A renewed state-individual relationship: the 'socialised self' 94

Unfolding the locus of responsibility: topic-based promotions 95

Promoting shared responsibility: the glory of being employed and the common interest 103

Conclusions 106

References 107

CHAPTER 4. Maximising support for pension reform using policy experimentation, and the potential to backfire 109

4.1. Risks in the pension reform and the statecraft of policy experiments 110

4.2. Policy effects on how the public sees the locus of responsibility for pension contributions 121

4.3. The concurrent effects of experiments and media campaigns on political trust 130

Conclusions 138

Acknowledgements 139

References 140

CHAPTER 5. Falsification of 'manufactured compliance'and wider legitimation and governmentality issues 146

5.1. 'Falsification' and methods for exploring it 147

5.2. Different faces of compliance: the words in shadow 160

5.3. The dual track of political knowledge 169

5.4. Ignorance, apathy, and collective conservatism 174

5.5. Heterogeneity of social groups: education and generations 181

5.6. Heading (no)where: actions or agencies 186

Conclusions 190

References 192

CHAPTER 6. Pension issues, state governmentality, and falsified compliance in a comparative perspective 197

6.1. Government and legitimation issues in China 198

6.2. Welfare reforms and state rationales in a comparative lens 204

Conclusions 211

References 212

Appendix A. Data explanation and model validations 216

Appendix B. Data replication codebooks 249

Bibliography 255

Figure I.1. Levels of economic development and the type of polity in China, 1950-2020 20

Figure I.2. Education and urbanisation development in China, 1950-2020 22

Figure 1.1. Thought map of compliance typology and respective statecraft 36

Figure 2.1. The timeline of segmented pension plan reforms, 1955-2011 52

Figure 2.2. Pension benefit for enterprise employees (averaged), 1995-2015 61

Figure 3.1. Correlations of topics 75

Figure 3.2. Topic proportions by year: economic reform and pension reform for enterprise employees 78

Figure 3.3. Topic proportions by year: birth control 84

Figure 3.4. Topic proportions by year: social justice and rural migrants 91

Figure 3.5. Topic by covariate: different types of responsibility emphasised 96

Figure 3.6. Some other topics by covariate: different types of responsibility emphasised 98

Figure 4.1. Visualisation of three waves pilot policy 125

Figure 4.2. Provincial variations of the dependent variable: locus of responsibility perception 125

Figure 4.3. Provincial variation of local official 'policy propaganda' efforts 126

Figure A.1. Urban labour types: employment in different types of units 217

Figure A.2. Number of documents in the full corpus 220

Figure A.3. Optimal topic number with Topicmodels validation 1 221

Figure A.4. Optimal topic number with Topicmodels validation 2 222

Figure A.5. Optimal topic number with perplexity 223

Figure A.6. Optimal topic number with STM validation 1 224

Figure A.7. Optimal topic number with STM validation 2 225

Figure A.8. Flowchart of hand coding 233

Figure A.9. Time trend of provincial index 239

Rapid economic growth is often a disruptive social process threatening the social relations and ideologies of incumbent regimes. Yet far from acting defensively, the Chinese Communist Party has lead a major social and economic transformation over forty years, without yet encountering fundamental challenges subverting its rule. A key question for political sociology is thus - how have the logics of China's governmentality been able to help maintain compliance from the governed while acting so radically to advance the state's growth priorities?

This book explores the issue by analysing the detailed trajectories, rationale, and effects of China's pension reforms. It uses strong methods, including institutional analysis of resource allocation in the multiple pension schemes and programmes, and quantitative text analysis of the knowledge construction in official discourse along with the reforms. Causal identification estimates the effects of key policy instruments on public opinion about pension responsibility and political trust. Moving beyond the pension issues, the analysis discusses with qualitative evidence why falsified compliance might exist in China's society and the mechanisms that may lie behind it. Where active counter-conduct (such as resistance) is confined, individuals may choose cognitive rebellion and falsify their public compliance.

The Chinese state's strategy to generate public compliance is hybrid, organic, and dynamic. The state rules society by its customised governance design and constant adjustments. Public compliance is not only acquired through 'buying off' the public with governmental performance and transfer benefits, but is also manufactured through achieving cultural changes and new ideological foundations for general legitimation.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

| 전화번호 |

|---|

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 번호 | 발행일자 | 권호명 | 제본정보 | 자료실 | 원문 | 신청 페이지 |

|---|

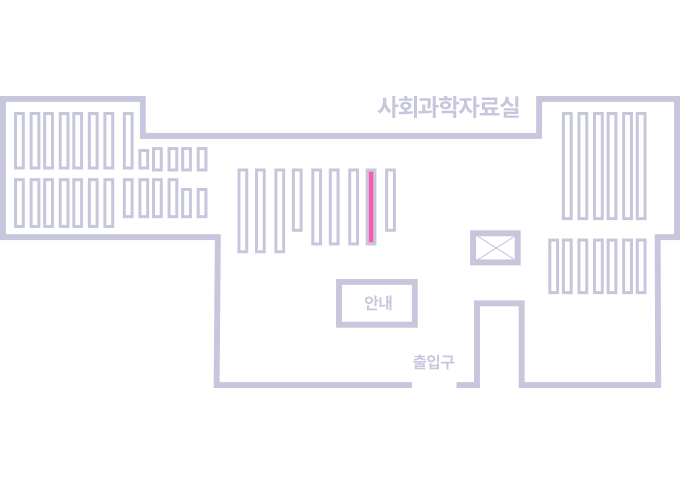

도서위치안내: / 서가번호:

우편복사 목록담기를 완료하였습니다.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

저장 되었습니다.