권호기사보기

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 대표형(전거형, Authority) | 생물정보 | 이형(異形, Variant) | 소속 | 직위 | 직업 | 활동분야 | 주기 | 서지 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 연구/단체명을 입력해주세요. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

* 주제를 선택하시면 검색 상세로 이동합니다.

Title page 1

Contents 5

Foreword 14

Acknowledgments 16

Summary 20

Glossary 23

Abbreviations 26

Overview: Making a Miracle 28

In brief 28

'To get rich is glorious' 29

One trap or two? 31

Investment, infusion, and innovation-additively and progressively 32

The economics of creative destruction 37

Striking the right balance 44

The road ahead 53

Notes 55

References 55

Part 1. Middle-Income Transitions 58

1. Slowing Growth 60

Key messages 60

Introduction 60

Growth in middle-income countries 61

Measuring progress through the middle stages of development 64

Growth in middle-income countries is slower 67

Notes 72

References 72

Spotlight 74

2. Structural Stasis 79

Key messages 79

Introduction 79

Economic development = structural change 81

Infuse first, then innovate 82

Notes 93

References 93

3. Shrinking Spaces 95

Key messages 95

Introduction 95

Fragmenting international trade 98

Elevated debt 99

Climate action 101

Notes 104

References 104

Part 2. Creative Destruction 106

4. Creation 109

Key messages 109

Creation: The protagonist of economic growth, where incumbents create value alongside entrants 109

Creative destruction: Three decades of increasingly refined analysis 112

In middle-income countries, too few small entrants disrupt, and too few large incumbents innovate or infuse global technologies 115

How governments stifle firms' incentives to grow, infuse global technologies, and innovate 120

Modernizing data and diagnostic tools to understand and regulate creative destruction-from X-rays to MRIs 128

Notes 130

References 130

5. Preservation 133

Key messages 133

Preservation is an antagonist of creation because it is also an antagonist of destruction 133

Talent drives economic progress, but social immobility holds back the development of talent 135

Elite pacts perpetuate social immobility and preserve the status quo 139

Patriarchal gender norms hold back a large proportion of the population 147

The cost of social immobility and preservation: Holding back the energies that drive creation 151

Notes 153

References 154

6. Destruction 158

Key messages 158

Destruction: To be expected, managed, and mitigated 158

The climate and energy crises could trigger restructuring and reallocation 160

Destruction without creation: The risks of becoming stranded nations 174

Notes 178

References 179

Part 3. Making Miracles 182

7. Disciplining Incumbency 184

Key messages 184

Balancing incumbents' innovation and abuse of dominance 184

Updating institutions to weaken the forces of preservation 186

Incentives for incumbents to strengthen creation 195

Interventions to correct errant behavior by incumbents 202

Notes 206

References 207

8. Rewarding Merit 211

Key messages 211

Moving forward by promoting merit activities 211

The economic and social mobility of people 212

The value added by firms 220

Reducing an economy's greenhouse gas emissions 229

Notes 235

References 236

9. Capitalizing on Crises 242

Key messages 242

Using crises to destroy outdated arrangements 242

Globalizing decarbonization 243

Expanding low-carbon infrastructure 249

Decoupling economic growth and emissions 253

Notes 260

References 261

Tables 13

Table O.1. World Bank country classifications and selected global indicators, 2022 31

Table O.2. To achieve high-income status, countries will need to recalibrate their mix of investment, infusion, and innovation 34

Table O.3. The 3i strategy: What countries should do at different stages of development 54

Table P1.1. World Bank country classifications and selected global indicators, 2022 58

Table S.1. Suggested indicators provide a clear picture of the underlying structure of an economy 76

Table 2.1. Middle-income countries will need to engineer two successive transitions to develop economic structures that can sustain high-income status 80

Table 4.1. Examples of possible effects of market power on development outcomes 127

Figures 8

Figure O.1. Income per capita of middle-income countries relative to that of the United States has been stagnant for decades 30

Figure O.2. If capital accumulation were enough, work in middle-income countries would be nearly three-quarters as rewarding as in the United States,... 32

Figure O.3. Economies become more sophisticated as they transition from middle-income to high-income status 33

Figure O.4. Middle-income countries must engineer two successive transitions to move to high-income status 34

Figure O.5. In the Republic of Korea, Poland, and Chile, the rapid growth from middle- to high-income status has been interspersed with economic crises 35

Figure O.6. From infusion to innovation in the Republic of Korea 36

Figure O.7. Over the last four decades, as the Republic of Korea's labor productivity relative to that of the United States continued to climb,... 38

Figure O.8. Three views of creative destruction 39

Figure O.9. Creation is a weak force in middle-income countries, where it is characterized by a rampant misallocation of resources 41

Figure O.10. Middle-income countries have to strike a balance among creation, preservation, and destruction 44

Figure O.11. In emerging market and developing economies, few companies are funded by venture capital or private equity 48

Figure O.12. Countries with large, successful diasporas have the highest potential for knowledge transfers 50

Figure O.13. In low- and middle-income countries, the cost of capital for renewables is high 53

Figure 1.1. A handful of economies have transitioned from middle-income to high-income status over the last three decades 62

Figure 1.2. Income per capita of middle-income countries relative to that of the United States has been stagnant for decades 63

Figure 1.3. Sustained growth periods are short-lived, even in rapidly growing economies 67

Figure 1.4. Growth slowdowns are most frequent when countries' GDP per capita is less than one-fourth of the United States' 70

Figure 1.5. Growth is expected to slow down as countries approach the economic frontier (United States) 71

Figure 1.6. Weak institutions hasten and worsen growth slowdowns 71

Figure 2.1. As economies develop, capital accumulation brings diminishing returns 81

Figure 2.2. A middle-income country will need to engineer two successive transitions to achieve high-income status: Infusion, followed by innovation 82

Figure 2.3. The demand for highly skilled workers increases in middle-income countries 84

Figure 2.4. STEM graduates are increasingly concentrated in middle-income countries, thereby increasing opportunities for technology infusion 85

Figure 2.5. Calibrating policies to a country's stage of development: From imitation to innovation in the Republic of Korea 86

Figure 2.6. The innovation gap between high-income countries and others is substantial 90

Figure 2.7. Middle-income countries significantly lag behind high-income countries in research capacity 90

Figure 3.1. Globally, harmful trade policies outnumber helpful trade policies 98

Figure 3.2. Harmful interventions in the global semiconductor trade have skyrocketed since 2019 99

Figure 3.3. Most developing economies are more severely indebted than ever 100

Figure 3.4. Debt service payments in emerging markets and middle-income countries may skyrocket as the cost of borrowing soars 101

Figure 3.5. In middle-income countries, the energy intensity and carbon intensity of energy consumption are quite high 102

Figure 3.6. In middle-income countries, the weighted average cost of capital for utility-scale solar power projects is substantially higher than the cost... 103

Figure 3.7. Low- and middle-income countries are exposed to similar levels of risk from climate change, and they have less adaptive capacity 104

Figure P2.1. Rebalancing the forces of creation, preservation, and destruction to advance infusion and innovation 108

Figure 4.1. Both entrants and incumbents create value and reinforce one another's growth through competition in India's computing services industry 110

Figure 4.2. The interactions between entrants and incumbents set the pace of creative destruction 111

Figure 4.3. Entrants drive growth: Insights from Aghion and Howitt's seminal paper on creative destruction 112

Figure 4.4. Entrants and incumbents drive growth through turnover and upgrading: Insights from Akcigit and Kerr's refined approach to creative destruction 113

Figure 4.5. Contrasting examples of innovation: Growth is driven by entrants in the United States and by incumbents in Germany 114

Figure 4.6. Entrants and incumbents can reinforce one another's growth: The case of the US business services industry 115

Figure 4.7. A cartelized industry suppresses innovation and dynamism: Evidence from the Japanese auto parts sector 116

Figure 4.8. In middle-income countries, the growth rate of firms across their life cycles is much lower than in the United States 119

Figure 4.9. Microenterprises dominate firm size distributions in India, Mexico, and Peru 120

Figure 4.10. Young firms-not small firms-create the most jobs (net) in the United States 121

Figure 4.11. Productivity-dependent distortions are more severe in low- and middle-income countries 125

Figure 4.12. Management practices are worse in economies with more policy distortions 126

Figure 5.1. The share of skilled workers in large firms increases with GDP per capita 136

Figure 5.2. Higher inequality is associated with higher intergenerational immobility 138

Figure 5.3. Intergenerational mobility of skilled workers matters more for middle-income countries than for low-income countries 139

Figure 5.4. High inequality within cities is associated with low social mobility from one generation to the next 142

Figure 5.5. In many middle-income countries, movement of workers from one part of the country to another is more limited than in high-income... 145

Figure 5.6. In many middle-income countries, migration costs are higher for individuals without high levels of education 146

Figure 5.7. There is a substantial gap between low- and high-income countries in female educational attainment 148

Figure 5.8. Female labor force participation is low in the Middle East and North Africa and in South Asia 148

Figure 5.9. Female labor force participation has evolved differently across countries 149

Figure 5.10. The share of female professionals has risen in some countries but not others 149

Figure 5.11. Globally, women own a smaller share of firms than men 150

Figure 5.12. Women lag behind men in having financial accounts 151

Figure 6.1. Learning by doing in the manufacture of key low-carbon technologies has resulted in rapid cost declines 162

Figure 6.2. The diffusion of low-carbon technologies is rapidly accelerating 163

Figure 6.3. Low-carbon innovation is driving the emergence of new spatial clusters, start-ups, and financing 165

Figure 6.4. The rate of adoption of clean energy technologies is growing more rapidly in middle-income countries than in high-income countries,... 168

Figure 6.5. Clean energy technology value chains are still dominated by high-income countries and China 170

Figure 6.6. Costa Rica and China are the global front-runners in jobs related to low-carbon technologies 171

Figure 6.7. Most of the countries currently "locked in" to declining brown industries are middle-income countries 176

Figure 7.1. In Italy, market leaders increase their political connections while reducing innovation 185

Figure 7.2. Promoting contestability through institutions, incentives, and interventions 186

Figure 7.3. In many middle-income countries, markets are dominated by a few business groups, as a survey suggests 187

Figure 7.4. In middle-income countries, restrictive product market regulations are pervasive 188

Figure 7.5. In middle-income countries, both economywide and sectoral input and product market regulations are more restrictive than in high-income countries 189

Figure 7.6. The BRICS and large middle-income countries have a significant presence of publicly owned enterprises and governance frameworks that stifle competition 190

Figure 7.7. A state presence has important effects on firm entry, market concentration, and preferential treatment 191

Figure 7.8. State-owned enterprises dominate coal power generation, while the private sector leads in modern renewable energy 192

Figure 7.9. In low- and middle-income countries, state-owned enterprises are the largest investors in fossil fuel energy generation 192

Figure 7.10. Foreign technology licensing is limited among middle-income country firms 196

Figure 7.11. Competition authorities in middle-income countries need more capacity to deal with sophisticated policy problems 204

Figure 8.1. Middle-income countries that transitioned to high-income status first focused on foundational skills 213

Figure 8.2. Countries at lower levels of development have more opportunities for potentially productivity-enhancing job reallocation 222

Figure 8.3. The number of countries creating special enforcement units for large taxpayers has increased 223

Figure 8.4. Improvements in allocative efficiency in Chile, China, and India have been driven by reducing productivity-dependent distortions 224

Figure 8.5. In emerging market and developing economies, few companies are funded through venture capital or private equity 228

Figure 8.6. Indirect carbon pricing such as energy taxes is the strongest price signal 231

Figure 8.7. In some middle-income countries, the prices of renewable energy through competitive auctions have reached record lows 233

Figure 9.1. Use of globalized value chains for solar panels results in faster learning and lower global prices 244

Figure 9.2. Middle-income countries can support global decarbonization by becoming global suppliers of "granular" (type 1 and type 2) 245

Figure 9.3. Extraction and processing of critical minerals for the clean energy transition remain highly concentrated in certain countries 246

Figure 9.4. Many middle-income countries have untapped potential to manufacture green products 247

Figure 9.5. All industrial policy implementation and green industrial policy implementation are correlated with GDP per capita 248

Figure 9.6. Countries must clear hurdles for both efficient domestic investment and foreign investment in renewable energy 250

Figure 9.7. In many middle-income countries, it is economically efficient to expand renewable energy 251

Figure 9.8. In low- and middle-income countries, the cost of capital for renewables is high 252

Figure 9.9. Today's upper-middle-income countries are more energy efficient than upper-middle-income countries in the past 253

Figure 9.10. Carbon emissions per unit of GDP have been declining worldwide 254

Figure 9.11. High-income countries have succeeded in reducing overall emissions by curbing energy intensity 255

Figure 9.12. The world is slowly transitioning away from fossil fuels 256

Boxes 7

Box O.1. Who and what are incumbents? Leading firms, technologies, nations, elites-and men 39

Box 1.1. Misunderstanding through misclassification 64

Box 1.2. A growth superstar: How the Republic of Korea leveraged foreign ideas and innovation 68

Box 1.3. Identifying growth slowdowns 69

Box 2.1. The Meiji Restoration reconnected Japan with global knowledge 86

Box 2.2. Three ways to evade the middle-income trap: Swiftly (Estonia), steadily (Poland), or slowly (Bulgaria) 87

Box 2.3. The magic of investment accelerations 91

Box 3.1. Graying growth 96

Box P2.1. Joseph Schumpeter and creative destruction 107

Box 4.1. Vibrant corporate R&D, connected places, mobile people, and successfulmarkets for patents: How the United States nurtured 117

Box 4.2. Examples of size-dependent policies 121

Box 4.3. The productivity effects of credit misallocation and capital market underdevelopment 124

Box 5.1. Firms with better-educated managers adopt more technology 137

Box 5.2. Living in favelas makes it more difficult to get a job 144

Box 5.3. Global Gender Distortions Index: Measuring economic growth lost to gendered barriers 152

Box 6.1. The diffusion of low-carbon technologies as defined and measured in this chapter 161

Box 7.1. A digital tool helps female entrepreneurs obtain capital and training in rural Mexico 195

Box 7.2. Technology for market access 197

Box 7.3. Supplier development programs to connect small firms with large firms 198

Box 7.4. Turning brain drain into brain gain 200

Box 7.5. Tackling anticompetitive practices increases incumbents' innovation incentives 202

Box 8.1. Developing foundational skills: Learning from Finland and Chile 214

Box 8.2. Promoting better student choices with digital tools 217

Box 8.3. Improving students' test scores by using online studying assistance from the Khan Academy 218

Box 8.4. Catching up by opening up and modernizing firms: The Spanish growth miracle 225

Box 8.5. Productivity growth can slow deforestation in Brazil 229

Box 8.6. Correcting abuses of dominance in electricity markets 234

Box 9.1. Technologies that can act as "stabilizers" of energy supply 258

Maps 13

Map 6.1. In 2022, one-third of online job postings related to low-carbon technologies were in middle-income countries 164

Map 6.2. Limited or outdated electricity transmission networks serve as barriers to the entry of renewable sources 173

Map 6.3. Low-carbon technology jobs in China are growing in manufacturing hubs on the southeast coast, whereas fossil fuel jobs are close to coal mines 177

Box Figures 9

Figure B2.3.1. Investment growth accelerations: Colombia, Republic of Korea, and Türkiye 92

Figure B3.1.1. Today's middle-income countries are aging more rapidly than high-income countries did in the past 96

Figure B4.1.1. The number of patents filed by corporations with the US Patent and Trademark Office has skyrocketed since 1880 117

Figure B4.3.1. Productivity-dependent financial distortions, by GDP per capita 124

Figure B5.1.1. Better-educated managers are more likely to adopt technology in middle-income countries 137

Figure B5.2.1. Slum residents in Rio de Janeiro identified their residence in a favela as the largest impediment to getting a job 144

Figure B7.4.1. Some countries are strongly positioned to benefit from knowledge spillovers from their diaspora 201

Figure B7.5.1. In Colombia, after a cartel is sanctioned, market outcomes improve through the entry and growth of previously lagging firms 203

Figure B7.5.2. In Colombia, after an abuse of dominance case, positive market outcomes are driven by improvements in leading firms 203

Figure B8.5.1. Amazon deforestation falls when Brazilian productivity rises 230

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

| 전화번호 |

|---|

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 번호 | 발행일자 | 권호명 | 제본정보 | 자료실 | 원문 | 신청 페이지 |

|---|

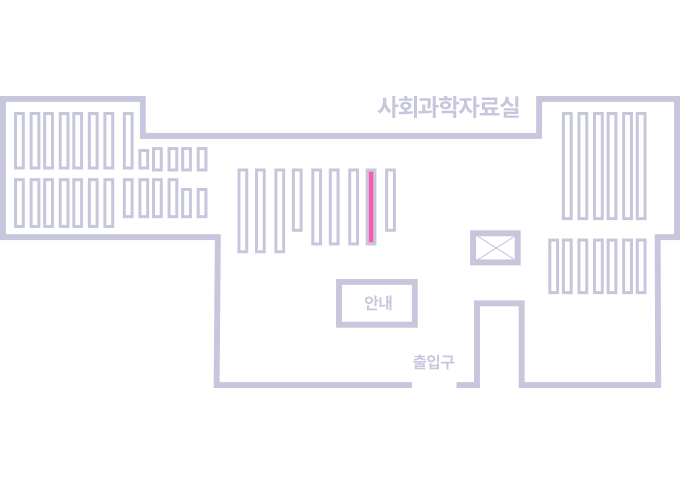

도서위치안내: / 서가번호:

우편복사 목록담기를 완료하였습니다.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

저장 되었습니다.