권호기사보기

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 대표형(전거형, Authority) | 생물정보 | 이형(異形, Variant) | 소속 | 직위 | 직업 | 활동분야 | 주기 | 서지 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 연구/단체명을 입력해주세요. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

* 주제를 선택하시면 검색 상세로 이동합니다.

Title page

Contents

Executive Summary 4

Key finding #1: Underrepresented populations disproportionately live in rural areas, work in agriculture, and lack access to critical public goods and services 5

Key finding #2: Underrepresented populations are less exposed to ambient air and water pollution, but may be more impacted by these, possibly due to... 6

Key Finding #3: Underrepresented populations are more exposed to-and more impacted by-land degradation and deforestation 7

But there is an exception to the deforestation relationship in Latin America, where deforestation on Indigenous lands is lower than on non-Indigenous lands 8

Key finding #4: Underrepresented populations have fewer options and face starker trade-offs between economic opportunities and environmental quality 8

Breaking the cycle 9

Policy actions when authorities are favorable to change 9

Policy actions in adversarial environments 10

Chapter 1. Environment and inclusion 11

Exclusion and environmental degradation 14

The focus of this report 15

References 21

Chapter 2. Public services for underrepresented populations: from infrastructure to critical resources 25

At a glance 25

2.1. Access to public assets and services 26

2.2. The incidence of environmental disamenities 29

References 32

Chapter 3. Fissured landscapes and divided waters: uncovering social cleavages 36

At a glance 36

3.1. Exposure to deforestation 37

3.2. Forest loss and cascading health impacts 40

3.3. Exposure to land degradation 43

3.4. Productivity losses and health impacts of poor soils 48

3.5. Gender dimensions 50

3.6. The way forward 52

References 53

Chapter 4. Disparities in Air Pollution 58

At a glance 58

4.1. Exposure to air pollution 58

4.2. Trade-offs between income and air quality 63

4.3. Consumption patterns and air pollution 65

The way forward 68

References 68

Chapter 5: Policy options for breaking the cycle of environmental degradation and social exclusion 71

At a glance 71

5.1. Inclusive policies and environmental policies are not always well-aligned 72

5.2. When objectives are shared: working within the system to empower marginalized communities 75

5.3. When objectives differ: best-feasible policy approaches 79

Public Engagement 80

Coalition Building 81

5.4. The way forward 83

References 83

Annex I: Maximizing overall welfare - A policy bundle 86

Annex II: Bridging gaps - A comparative framework for examining the welfare gap 88

Figure 1.1. Population shares at risk of underrepresentation by country income levels 17

Figure 2.1. Access to basic public services at the household level, by representation status 27

Figure 2.2. Estimated coefficients of public good access versus underrepresentation risk, over gross domestic product (GDP) quartiles 29

Figure 2.3. Exposure to land, air, and water degradation, by representation status 30

Figure 2.4. Agricultural employment and urbanization rates by, representation status 31

Figure 3.1. Social exclusion, Indigenous populations, and deforestation 38

Figure 3.2. Access to piped water, by exclusion status and household income 41

Figure 3.3. Global loss of net primary productivity in the degrading areas between 1981 and 2021 45

Figure 3.4. Vulnerability to sexual attacks when fetching water: underrepresented v non-underrepresented women 51

Figure 4.1. Global population-weighted exposure to PM2.5 air pollution relative to the year 2000 59

Figure 4.2. Exposure to PM2.5 concentrations (ug/m3) by country income group 60

Figure 4.3. Differential exposure to hazardous PM2.5 based on relative wealth and underrepresentation risk 60

Figure 4.4. Wealth effects of mining on households 65

Figure 4.5. Household budget share of energy type (high v low-polluting), by country income group 66

Figure 4.6. EECs for cooking fuels by representation-status 67

Figure 4.7. EECs for motorcycle ownership for underrepresented and non-underrepresented groups 67

Figure 5.1. A policy matrix for examining the welfare gap 74

Boxes

Box 1.1. Approaches for measuring ethnic diversity 13

Box 1.2. What are the benefits of inclusive decision-making? 15

Box 1.3. How is the URRI built? 18

Box 3.1. Gentle resistance: the bottom-up Chipko movement 39

Box 3.2. Estimating unequal health impacts from forest loss due to waterborne diseases 40

Box 3.3. Causal analysis of the deforestation linkages with malaria transmission 42

Box 3.4. Dependency on forests in Nepal is mediated by consumption expenditures 44

Box 3.5. The evolution of measuring land degradation 46

Box 3.6. Underrepresentation risk and the determinants of land degradation methodology 47

Box 3.7. Zinc deficiency in soil and health impacts on underrepresented populations 49

Box 4.1. Prioritizing access to economic opportunities over environmental health: evidence from Santiago 61

Box 4.2. The impact of household air pollution on women and children 62

Box 4.3. Mining as a contributor to local air pollution 63

Box 4.4. Environmental Engel curves 65

Box 5.1. Tinbergen's Rule - Aligning policy instruments to achieve multiple targets 73

Box 5.2. Integrated Conservation and Development Projects 75

Box 5.3. The promise and perils of decentralization 76

Box 5.4. Water, women, and the importance of voice in decision-making 77

Box 5.5. The World Bank's Environmental and Social Framework 79

Box 5.6. African Parks - a model for sustainable growth in low-capacity environment 81

Box Figures

Figure B1.3.1. Correlations between URRI and other socioeconomic measures 20

Figure B3.3.1. Soybean crop growth and trends in an Amazonian country, 2001-23 43

Figure B3.4.1. Access to public forests and private trees, by consumption quintiles 44

Figure B3.4.2/Figure B3.4.12. Perceived value of NTFPs, compared to annual expenditure on food purchased and annual total consumption expenditure 44

Figure B4.4.1/Figure B4.4.2. Block-level population shares in Santiago for immigrant (left) and Indigenous (right) households 61

Figure B4.4.2/Figure B4.4.3. Historical street map of Santiago around 1920 (left) and in 2022 (right) 62

Figure B4.3.1. Effect of mine opening on air pollution measured via mean AOD 64

Figure B4.4.1. Stylized EEC relationships for normal and inferior goods 65

Annex Figures

Figure A.5.1. A policy bundle with no externalities 86

Figure A.5.2. Economic and environmental policies with externalities 87

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

| *전화번호 | ※ '-' 없이 휴대폰번호를 입력하세요 |

|---|

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 번호 | 발행일자 | 권호명 | 제본정보 | 자료실 | 원문 | 신청 페이지 |

|---|

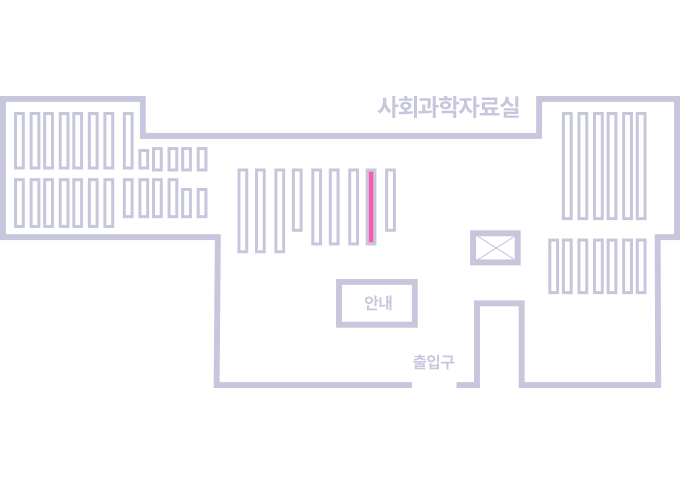

도서위치안내: / 서가번호:

우편복사 목록담기를 완료하였습니다.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

저장 되었습니다.