권호기사보기

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 대표형(전거형, Authority) | 생물정보 | 이형(異形, Variant) | 소속 | 직위 | 직업 | 활동분야 | 주기 | 서지 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 연구/단체명을 입력해주세요. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

* 주제를 선택하시면 검색 상세로 이동합니다.

Title page

Contents

List of Abbreviations 9

Acknowledgments 11

Executive Summary 12

1. Introduction 21

1.1. Country Context 21

1.2. About this Report 30

1.3. Poverty Measurement 31

2. Poverty and Inequality Patterns, Trends, and Drivers 34

2.1. The Current Situation 35

2.2. Trends and Drivers 45

2.3. Conclusion 57

3. Poverty, Vulnerability, and Resilience 61

3.1. Hazards, Exposure, and Vulnerability 62

3.2. Coping Mechanisms 74

3.3. Conclusion 77

4. Human Capital and Labor Market 79

4.1. Overview of Labor Force and Employment Conditions 80

4.2. Key Labor Demand and Supply Factors 83

4.3. Conclusion 90

5. Poverty and Social Protection 93

5.1. Coverage of the Current Social Assistance Programs 95

5.2. Improving SP/ASP to Better Protect the Poor 99

5.3. Conclusion 104

References 106

Annex A. Poverty Measurement in Tonga 111

Annex B. SWIFT: Survey-to-Survey Imputation for Poverty Trend Analysis 114

Annex C. The Unbreakable Simulation for the Poverty Impacts of Natural Disaster Events 119

Annex D. Patterns of Remittances Received in 2021 122

Annex E. Government Responses to Recent Crises 126

Annex F. Additional Tables and Figures 129

TABLE 1. The primary focus of this report is monetary poverty based on the national cost-of-basic-needs poverty line 32

TABLE 2. Household consumption distribution is skewed 36

TABLE 3. Projection results based on macroeconomic indicators suggest similar poverty trends 48

TABLE 4. Without remittances, poverty could have been higher by 5 to 10 percentage points 57

TABLE 5. Without mitigation measures, natural disasters could severely affect poverty 70

TABLE 6. Types of positions and skill requirements in the Pacific tourism sector 83

TABLE 7. The 2021 HIES sampling 111

TABLE 8. Spatial and temporal deflator 113

TABLE 9. Urban and Rural SWIFT models, created using HIES 2021 as training data 115

TABLE 10. Performance test results of urban and rural SWIFT models within HIES 2021 data 116

TABLE 11. Summary statistics of model variables for HIES 2015/16 and HIES 2021 116

TABLE 12. Poverty regression results 129

TABLE 13. Despite slight increases since 2015/16, labor force participation and employment rates are still lower among the poor 131

FIGURE ES1. Poverty and inequality dropped from 2015/16 to 2021 13

FIGURE ES2. Insufficient human capital contributes to skills mismatches 15

FIGURE ES3. With their limited coverage, SA programs have little impact on poverty 16

FIGURE ES4. Poorer households, including those with no employment, experienced stronger consumption growth between 2015/16 and 2021 17

FIGURE ES5. Poorer households are more exposed and vulnerable to natural hazards 19

FIGURE 1. Tonga's GDP growth was already weaker than other PICs before the COVID-19 pandemic 22

FIGURE 2. Multiple shocks slowed Tonga's economic growth in recent years 23

FIGURE 3. Tonga's smallness and remoteness stand out, constraining its economic potential 24

FIGURE 4. Sectoral composition in GDP and employment has been stable for a while 25

FIGURE 5. Tonga's human capital is lower than other upper-middle-income countries 25

FIGURE 6. The tourism sector was growing before COVID-19 26

FIGURE 7. The population has been slightly decreasing due to a decline in the fertility rate and out-migration 27

FIGURE 8. Remittances received have been fast rising, with the GDP share in Tonga becoming the world's highest 28

FIGURE 9. The economic impact of natural disasters has been sizable in Tonga 29

FIGURE 10. Consumption varies within and across island groups 37

FIGURE 11. Poverty is lowest in urban Tongatapu and highest in 'Eua and Ongo Niua 39

FIGURE 12. Poverty rates are higher in 'Eua and Ongo Niua 40

FIGURE 13. Two-thirds of the poor population live in Tongatapu 41

FIGURE 14. Tonga's poverty and inequality levels are lower than comparable countries 42

FIGURE 15. Food insecurity still prevails 43

FIGURE 16. Poverty is correlated with household education levels, income sources, and locations 44

FIGURE 17. Children and youth make up more than half of the poor population 45

FIGURE 18. GDI per capita, including remittances received, grew by 14 percent in real terms between 2015/16 and 2021 46

FIGURE 19. Poverty has likely dropped both in incidence and headcount 46

FIGURE 20. Household access to basic services has improved, with some islands lagging behind 50

FIGURE 21. Household ownership of key assets, including cars, improved 51

FIGURE 22. Poorer households gained more consumption growth, resulting in inequality reduction 52

FIGURE 23. Rural consumption growth drove poverty reduction 53

FIGURE 24. Remittances are a crucial income source, particularly for households with non-working heads 55

FIGURE 25. Remittances received increased both intensive and extensive margins 56

FIGURE 26. GDP-based projections imply Tonga's sustained poverty reduction 59

FIGURE 27. There are a range of negative effects of labor migration perceived by Tongans 60

FIGURE 28. Tonga has been frequently exposed to severe natural disaster events 63

FIGURE 29. Severe TCs can affect the whole population, while flooding is a more localized event 64

FIGURE 30. A large proportion of poorer households engage in subsistence agriculture 66

FIGURE 31. Phone surveys captured the socio-economic impacts of the HT-HH eruption and COVID-19 crises in 2022 67

FIGURE 32. Many households lost productive assets in disaster-struck islands 68

FIGURE 33. The size of simulated household consumption loss varies by location and baseline consumption levels 71

FIGURE 34. Experience of food insecurity significantly increased after the HT-HH eruption and the first COVID-19 lockdown 72

FIGURE 35. Inflation was exceptionally high in utilities, energy, and transport 73

FIGURE 36. High inflation in 2022 could have increased poverty by 5 percentage points if household income did not increase 74

FIGURE 37. Unsustainable coping strategies were common among poorer households to deal with the crises 75

FIGURE 38. Poor households need different types of solutions 76

FIGURE 39. The poor are more likely to be inactive and, among employed, work in the agriculture, manufacturing, and construction sectors 81

FIGURE 40. More working-age Tongans complete tertiary education 85

FIGURE 41. Children from poor households are less likely to be enrolled in school 86

FIGURE 42. Consumption returns to education are higher among men and urban residents 87

FIGURE 43. Tonga successfully reduced stunting 88

FIGURE 44. Obesity and NCDs are prevalent and getting worse among Tongan adults 89

FIGURE 45. Internet usage is relatively low in 'Eua and Ongo Niua 90

FIGURE 46. Many poor individuals are not covered by SA programs 97

FIGURE 47. The SA programs cover the elderly population well due to the SWS 97

FIGURE 48. The SA programs have little to no impact on poverty, except for the elderly 99

FIGURE 49. Increasing SA benefits based on the current targeting has a limited impact on poverty 100

FIGURE 50. Increasing benefits and improving targeting will reduce a great amount of poverty 101

FIGURE 51. Well-targeted transfers can reduce the disaster impact effectively and efficiently 103

FIGURE 52. Combined with increases in remittances, new transfers would further reduce post-disaster poverty 104

FIGURE 53. The amount of remittances received by Tongan households is constant relative to their consumption levels 124

FIGURE 54. Households in Ha'apai, 'Eua, and Ongo Niua are less likely to receive remittances 125

FIGURE 55. Tonga's access level to basic services is high among the PICs 131

FIGURE 56. Poor households tend to have inferior types of basic services 132

FIGURE 57. Migrant workers send remittances to support the daily expenses of their families in Tonga 132

FIGURE 58. Household asset ownership declined slightly after the dual shock in 2020 133

FIGURE 59. Young women are more likely to be in NEET 133

FIGURE 60. The gender gap in employment is significantly higher between married men and women 134

FIGURE 61. Women are more likely to work in high-skill service sector jobs or self-employed craft work 134

FIGURE 62. Around 80 percent of working-age adults own mobile phones 135

FIGURE 63. Tonga in the Pacific Region 135

Boxes

Box 1. Poverty measurement with HIES 2021 32

Box 2. Establishing comparable welfare and poverty measures between 2015/16 and 2021 47

Box 3. Social costs of labor mobility 60

Box 4. World Bank high-frequency phone surveys in Tonga 67

Box 5. Tonga's National Social Protection Policy and SA programs 96

Box 6. Targeting mechanism for the CCT 102

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

| *전화번호 | ※ '-' 없이 휴대폰번호를 입력하세요 |

|---|

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 번호 | 발행일자 | 권호명 | 제본정보 | 자료실 | 원문 | 신청 페이지 |

|---|

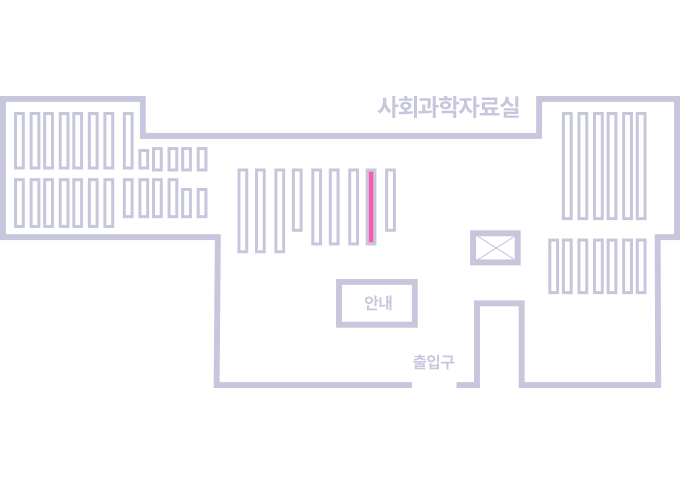

도서위치안내: / 서가번호:

우편복사 목록담기를 완료하였습니다.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

저장 되었습니다.