권호기사보기

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 대표형(전거형, Authority) | 생물정보 | 이형(異形, Variant) | 소속 | 직위 | 직업 | 활동분야 | 주기 | 서지 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 연구/단체명을 입력해주세요. | |||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

* 주제를 선택하시면 검색 상세로 이동합니다.

Title page 1

Contents 1

Abstract 3

1. Introduction 4

2. Data and Methodology 7

3. Results 9

3.1. Main Results 9

3.2. Robustness and Extensions 13

4. Conclusion 14

References 17

A. Appendix Figures and Tables 23

Tables 20

Table 1. Effects of Reproductive Technology on Child Care Employment 20

Table 2. Effects of Reproductive Technology on the Schooling Attainment of Child Care Workers 21

Table 3. Effects of Reproductive Technology on Child Care Workers' Wages 22

Figures 19

Figure 1. Share of Working-Age Women Employed in the Child Care Industry, by Education Level and Birth Cohort 19

Appendix Tables 25

Table A1. Robustness Checks 25

Table A2. Results from the Leave-One-Out Analysis 26

Table A3. Effects of Reproductive Technology, by Race 27

Appendix Figures 23

Figure A1. Number of States Granting Legal and Confidential Access to the Pill, by Age, 1960 to 1976 23

Figure A2. Number of States Granting Legal and Confidential Access to Abortion, by Age, 1960 to 1976 24

The composition and quality of the child care workforce may be uniquely sensitive to changes in the complementarities between home production and market work.

This paper examines whether the expansion of oral contraceptives and abortion access throughout the 1960’s and 1970’s influenced the composition, quality, and wages of the child care workforce. Leveraging state-by-birth cohort variation in access to these reproductive technologies, we find that they significantly altered the educational profile of child care workers—increasing the proportion of less-educated women in the sector while reducing the share of highly-educated workers. This shift led to a decline in average education levels and wages within the child care workforce.

Furthermore, access to the pill and abortion influenced child care employment differently across settings, with center-based providers losing more high-skilled workers to alternatives with better career opportunities, and home-based and private household providers absorbing more low-skilled women, for whom child care may have remained a viable employment destination. Overall, our findings indicate that increased reproductive autonomy, while expanding women’s access to higherskilled and -paying professions, also resulted in a redistribution of skilled labor away from child care, which may have implications for service quality, child development, and parental employment.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

| *전화번호 | ※ '-' 없이 휴대폰번호를 입력하세요 |

|---|

| 기사명 | 저자명 | 페이지 | 원문 | 기사목차 |

|---|

| 번호 | 발행일자 | 권호명 | 제본정보 | 자료실 | 원문 | 신청 페이지 |

|---|

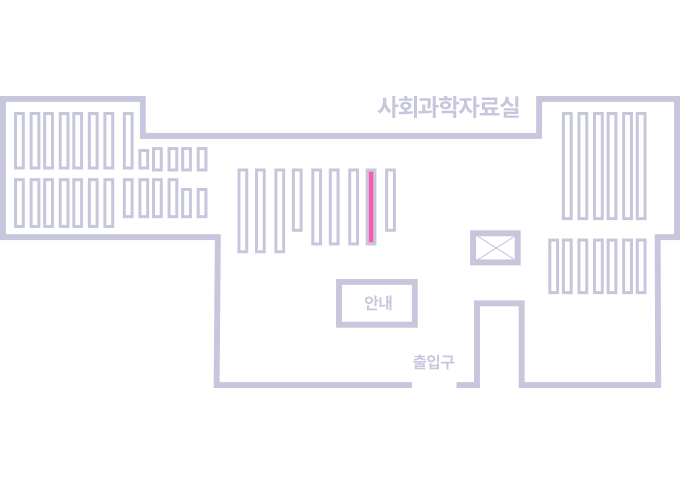

도서위치안내: / 서가번호:

우편복사 목록담기를 완료하였습니다.

*표시는 필수 입력사항입니다.

저장 되었습니다.